American sailors at Ford Island reacting to the explosion of the USS Shaw during the second wave of attacks.5

Posted On: December 30, 2019

It’s a day that generations would never forget, an event that shook America to its core and then into action: December 7, 1941. A date which has lived in infamy since Japanese forces surprise-attacked the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor on a quiet Sunday morning.

Tensions had been mounting between the U.S. and Japan over Japanese aggression towards China beginning as early as 1931, after Japan invaded Manchuria. Tensions escalated starting December 1937 (attack on USS Panay, the Allison incident, and the Nanking Massacre1) and again in the summer of 1940, when the U.S. halted exports of war related materials such as airplanes. In April 1940, President Roosevelt moved the Pacific Fleet from San Diego, CA to Hawaii, hoping to discourage Japanese aggression.

Although negotiations between the U.S. and Japan were underway through November 1941, tensions constantly mounted. The final U.S. counter-proposal required Japan to evacuate China and cease aggression against Pacific powers. It arrived in Japan on November 27. The Japanese task force had left for Pearl Harbor on November 26, for what they believed a preventative action to keep the U.S. from interfering in their military campaigns in Southeast Asia. Admiral Husband E. Kimmel at Pearl Harbor was notified on November 27 that “negotiations have ceased” and that “this dispatch is to be considered a war warning.”2

A deliberate and sudden attack

Library of Congress

Wreckage of USS Arizona

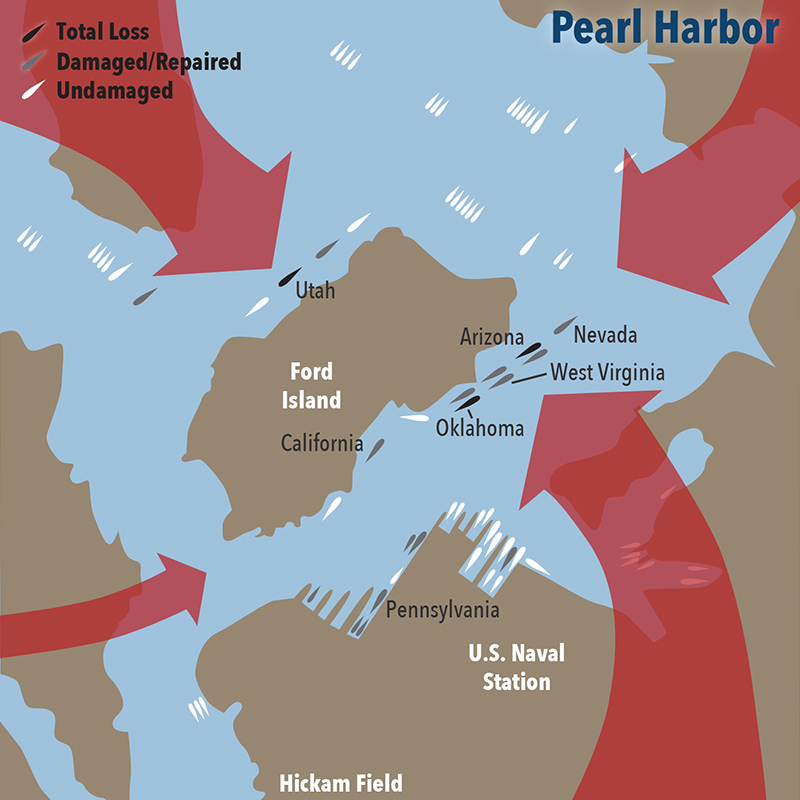

At 7:55 am, the first wave of nearly 200 Japanese aircraft arrived in Hawaii, attacking the ships docked in Pearl Harbor and the air stations at Hickam, Wheeler, Ford Island, Kaneohe and Ewa Field. Only 6 U.S. planes were able to make it airborne to repel this first wave of attack and while the antiaircraft crews on the battleships quickly jumped into action, they were not particularly effective. The USS Arizona, USS West Virginia, USS Oklahoma, USS California and USS Utah were all sunk or damaged, with most of the destruction occurring within 30 minutes.

The second wave began at 8:50 am, severely damaging the USS Nevada, USS Pennsylvania and two destroyers. The Japanese finally withdrew at 9:00 am, two hours after it began, leaving behind a nightmare of chaos, death and devastation.

Local recollections

Amongst the military personnel at Pearl Harbor that day was 1st Lt. Glen Richard Rosenberry of the Army Air Corps and ET 1/C Robert Abbott Coates (USS Nevada).

Glen Richard Rosenberry

Richard Rosenberry, born on November 19, 1921 in Ohio enlisted in the Army Air Corps in January 1940. He got to choose where he was stationed, and as most young men would, he chose Hawaii. He worked at Hickam Field, assigned yard work duties or whatever else needed done.

On December 7, Rosenberry heard a loud explosion. Running out onto the parade ground, he immediately got the picture; there were 5-6 Japanese planes flying over, strafing the runway and smoke was coming from Pearl Harbor. Rosenberry ran back inside to the armament office and was issued a British Enfield rifle, half a belt of machine gun ammo, and an order to do whatever was necessary.

After getting off a few shots, he noticed bombs falling from the sky. “I chose to face the bombs stretched out on the ground. The bombs hit and I was sucked up in a vacuum where the bomb actually exploded right behind me. I was sucked up in the air, where I was looking over the palm trees and into the second floor of the fire station… and then, of course, I immediately returned to earth…and bounced off the ground.”

USAF

Hickam Field, 1940. Pearl Harbor Navy Yard is in the upper left corner.

Feet hanging in the bomb crater, he looked around and saw a lot of wounded people and an unharmed weapons carrier truck. Despite the shrapnel in his left foot, he knew what he had to do. “I proceeded to get the weapons carrier and some other people helped me [load] it up with the wounded people that were there, and I drove them down to the base hospital. When we got there, there were some nurses and they took the ones that they thought were critically injured and then put some other ones in with me.” By that time, the weapons carrier was full of shrapnel and the engine was steaming. Rosenberry was issued a command car, and with a month-old Hawaiian driver’s license, drove the injured men to Tripler General Hospital.

“When they had unloaded the command car and they took care of the wounded, I looked down at the floor…and I noticed there was a lot of blood, and I realized that was my blood…So I decided maybe I had better go in and see if they could put a bandage on it or something. I went in and they took me up to a ward and sat me on a bed and put a basin under my foot. It wasn’t very long until a doctor came by…and he said ‘By God, put that man’s leg up in the air! Don’t just catch his blood, put it up in the air and put a bandage on it.’ So that’s what they did.”

Rosenberry was in the hospital until January 3 or 4, after finally receiving an operation on his foot on December 21. He received a Purple Heart for his actions at Pearl Harbor. Rosenberry headed for England in 1943 with the 492nd Bombardment Group of the 8th Air Force. In May 1944, he was shot down on his third mission and imprisoned until he returned home May 1945. Richard Rosenberry passed away May 2, 2014 at age 92, having lived much of his later life in Caldwell, Idaho.

Robert Abbott Coates

Bob Coates was born April 25, 1921 in Carey, Idaho. After attending Utah State, he joined the Navy in 1941 and was stationed on board the USS Nevada. The evening of December 6, 1941, Coates was on the list for an overnight liberty, a rare treat which meant he was allowed to sleep on land at a rec center.

“The next morning when I got up, I went to get a cup of coffee. I walked down this little old dirt road where this camp was…and this little old lady in a coffee shop was hollering about Pearl Harbor getting bombed. [I was like] what the heck, what are you talking about. I could hear that noise, rumbling and stuff in the background, but I thought it was the army having exercises—this was going on all the time. Then I saw this plane fly over, real low, just treetop low. There was another kid with me and I told him ‘look at that, they’re really trying to make this realistic, they’re even painting rising suns on their planes’. Then this woman starts hollering and I realized this was for real.”

“So I beat the heck out of there. I caught a ride into Pearl Harbor and when I came around where I could look into the harbor—I couldn’t see it until then—and my God, that was the awfullest feeling. I thought it was the end of the world because all I could see was smoke, and I could see my ship out in the middle of this.”

National Archives

USS Nevada temporarily beached on hospital point.

“It was the funniest darn feeling. I kind of liken it to…I read about horses when a barn lights on fire and you take the horse out, he will run right back into that, if you aren’t careful and tie him up. If he can, he’ll run right back into the burning barn, because that’s his home. Well, that was the way with me with the [USS] Nevada…that’s my home and I tried to get out there. I got a boat but…the ship was underway and they wouldn’t let me on it.”

Coates had arrived at the scene just as the second wave of attacks had started. After attempting to deliver him to his ship, the liberty boat he was on proceeded to drop other sailors off at their ships. After the last stop, Coates was en route back into the harbor when a Japanese plane strafed the area. Coates ran the boat aground in order to take cover under the cement stairs. After waiting it out and regaining his composure, Coates said “to hell with it. It’s not doing me good and nobody else, so I went back out and made it over to the landing and they gave me another boat.”

Coates spent the next two days ferrying supplies, yard workmen, and survivors around the harbor. “I was ferrying yard workmen and sailors out to these sunken ships and the ones that I went to most was the Oklahoma and the West Virginia. The Oklahoma had turned turtle, and they were trying to get people out of there. They had welding torches and everything trying to cut out the bottom of the ships, so they could get some of those people out that were trapped. I ran this boat back and forth all day.”

“It was a chaotic mess. There were all types of rumors that the Japanese were landing on the other side of the island. I didn’t sleep until the night of the 9th. I just passed out, I guess, woke up on a bench.”

After Pearl Harbor, Coates was reassigned to the USS San Francisco and participated in 17 major battles in the Pacific Theater. After his six years of enlistment, he worked as a civilian Electronic Technician for the Navy Department in California, eventually relocating back to Idaho to purchase a sheep ranch. Coates was a long-time supporter and friend of the Warhawk Air Museum and passed away April 13, 2011 at age 89.

Severe damage and lives lost

The toll was heavy on American troops and civilians. In total 2,4031 Americans were killed (including 68 civilians) and 1,1431 were wounded. Because the attacks were a surprise and occurred very early in the morning, and officers and senior personnel lived in housing on land, it’s believed that many of 2,008 sailor casualties were junior enlisted personnel—young men.1

Eighteen ships were sunk or run aground and more than 180 aircraft were destroyed. The Japanese lost fewer than 100 men.

One of the many American casualties was Idaho native QM 2/C Curtis James Haynes. Born in Arena Valley, Idaho in 1923, Haynes graduated high school in 1936 and joined the Navy. He was stationed on the USS Arizona. On February 11, 1942, Haynes’ mother, Evelyn received a letter from James Forrestal, acting secretary of the Navy, offering his “personal condolence in the tragic death of your son, Curtis James Haynes, Quartermaster, Second Class, United States Navy, which occurred at the time of the attack by the Japanese on December seventh.” His body was never found and is believed to be entombed in the USS Arizona.

Haynes’ death had a profound impact on his family. After the news, his brother Cooper joined the Navy aboard a hospital ship, his other brother Beuford joined the Naval Construction Battalions and helped build the airfield on Guam. Curtis’ finacée, Edith Marler, joined the WAVES. All returned home safely at the end of the war.

Haynes’ service memorabilia was donated to the Warhawk Air Museum in 2002 by his nephew.

All measures taken

The day after Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt delivered his famous Address to a Joint Session of Congress: “Yesterday, December 7, 1941 – a date which will live in infamy – the United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan.”4 An hour after he finished, Congress declared war on Japan. Germany and Italy, Japan’s allies, declared war on the U.S. on December 11, which the U.S. reciprocated the same day. The U.S. was officially at war on two fronts: the Pacific Theater and the European Theater.

Another consequence of the attack, and the subsequent Niihau incident, was the relocation of 110,000 Japanese-Americans, mostly from the West Coast, to internment camps. Canada followed this example, passing a War Measures Act which allowed for the forced removal of any and all Canadians of Japanese descent from British Columbia. 12,000 Japanese-Canadians were interned, 2,000 sent to road camps and 2,000 sent to sugar beet farms.1

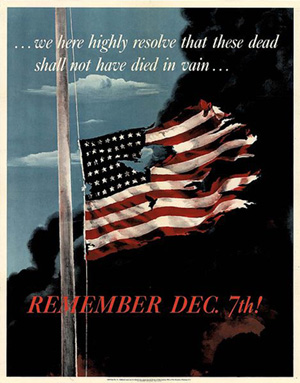

The attack at Pearl Harbor was a great motivator and was used frequently by the government and military in propaganda during WWII. Calls to “Avenge December 7th” and “Remember Pearl Harbor” were used to encourage enlistment and purchase war bonds. Before December 7, only 65% of the public supported helping the UK in the war and 39% supported war with Japan. After the attacks, that number rose to 97%.3

You can view pictures, medals, memorabilia and stories from Rosenberry, Coates and Haynes’ military service at the Warhawk Air Museum.

Resources

- Attack on Pearl Harbor. (2019, December 18). Retrieved December 20, 2019, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Attack_on_Pearl_Harbor.

- The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2019, December 2). Pearl Harbor attack. Retrieved December 20, 2019, from https://www.britannica.com/event/Pearl-Harbor-attack.

- Consequences of the attack on Pearl Harbor. (2019, December 22). Retrieved December 20, 2019, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Consequences_of_the_attack_on_Pearl_Harbor.

- "A Date Which Will Live in Infamy": Pearl Harbor Speech. (n.d.). Retrieved December 20, 2019, from https://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/document/pearl-harbor-speech/.

- The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2019, December 2). The attack. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/event/Pearl-Harbor-attack/The-attack#/media/1/448010/235618.

Tags: Displays|Veteran's Stories|WWII

Opens in new window

Opens in new window  Opens in new window

Opens in new window  Opens in new window

Opens in new window