Lt. Brand and Martha Painter

Posted On: February 13, 2020

For the love of letters

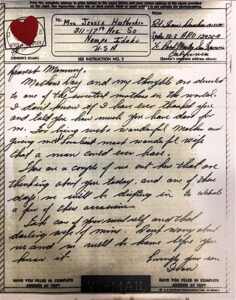

When pondering love during wartime, specifically World War I and World War II, most people immediately think of love letters. And for good reason. The Warhawk Air Museum itself is brimming with letters. Letters between sweethearts, spouses, siblings and parents. Letters full of passion, of hope, of worry.

Letters were the lifeblood of relationships of all kinds during WWI and WWII. They reminded soldiers, covered in mud on the frontlines, what they were fighting for and that somebody cared. For those at home, they brought a moment of relief and sense of connection. There is so much insight to be gained from taking a moment to read through these missives, and we highly encourage Warhawk visitors to do so–to learn about the people behind the many artifacts on display.

Though there are stories of couples meeting and falling in love exclusively through letters, most love letters were for those already in a relationship. So for those still single, what was preparing for a night-out like in a time of rationed makeup, toiletries, and clothing?

Keep Your Beauty on Duty

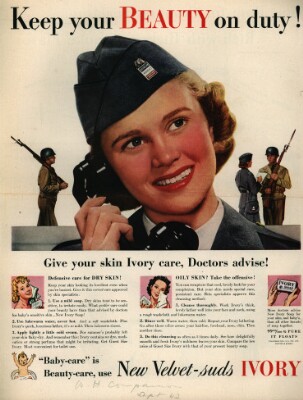

Women’s beauty occupied a strange space during the World Wars. In particular during World War II, the government and cosmetic companies propagandized beauty, grooming and makeup as a patriotic duty (“‘To look unattractive these days is downright morale-breaking and should be considered treason.’ So it was that a lipsticked American woman was a good American.”1), a coping mechanism, and even, in some sense, a weapon. Maintaining a sense of glamor in day-to-day life was a way to retain dignity, bravery (much like swiping on war paint), and, in a time of fear, worry and sadness, a little bit of fun.

With makeup seen as a symbol of a “free society worth defending”2, compounded by Hitler’s hatred of “made-up” women3, cosmetics companies jumped on the advertising possibilities. Even when supplies were no longer available to purchase, ads continued, asking women to use their makeup supplies wisely but never neglect their beauty. Elizabeth Arden was approached in 1940 to create a lipstick to perfectly match the red piping on women’s military uniforms. Thus women were issued an official military kit of matching “Montezuma Red” lipstick, cream blush and nail polish.4

For a woman looking to go out for an evening, perhaps at a local USO dance, the appropriate routine would include clear skin (Ivory soap was Doctor approved!), a touch of foundation and a puff of face powder (available for a time in the patriotic shape of a military cap), well-groomed brows, blackened lashes, a perfectly coiffed “Victory Roll”, and the ever important swipe of “Victory Red” (the civilian version of “Montezuma Red”, an exact reproduction available here).

However, as “essential” to the war effort as cosmetics were, they, like much else, suffered from rationing and shortages. Once a women’s closely hoarded stash of makeup was gone, alternatives had to be found. Lipstick could be replaced with a beetroot lip stain, boot-polish used as mascara (not recommended), and chalk-based powder and margarine-based foundation were made available by less-reputable sources5.

Hair short and fingernails clean

Men’s hair fashions have been dictated by military requirements since the Revolutionary War. From the low ponytail of the late 1700’s (banned in 1801 by Maj. Gen. James Wilkinson), to the short, neatly trimmed style of the Civil War, to the WWII mandate to “keep your hair cut short and your fingernails clean”, men’s hairstyles became shorter and shorter6.

Beards and mustaches were also mandated by the military. While beards and mustaches were allowed during the Civil War, the use of chemical warfare changed the game. Shaving became a requirement during WWI to ensure a “proper fit and seal on the gas mask and personal hygiene”6. Beards and mustaches continued to be outlawed during WWII, however due to razor shortages (an allowance of one blade per week) and the logistics of shaving in trenches, these requirements were more lax.

In an attempt to maintain grooming requirements, GIs were issued dopp kits by the US Army. The dopp kit (or toiletry kit) was created in 1920 by Charles Doppelt from Chicago and during WWII, he secured a contract with the Army to supply them to troops. A typical toiletry kit usually contained a razor, shaving soap or powder, comb, toothpaste or powder, mirror, toothbrush, and soap. The Gillette double-edged safety razor, introduced in 1895 and popularized during WWI, saw another burst in popularity during WWII, prompting the company to dedicate its entire production to the US military.

A soldier, finding himself attending a USO dance or event, was expected to be shaved and trimmed, with a clean and tidy uniform. Any laxness allowable at the front lines did not apply.

The fashion of utility7

Clothing, while rationed and limited, was another opportunity to show patriotism. The number of men and women in military uniform rose from 1.8 million in 1941, to 3.9 million in 1942, to more than 12 million in 1945. For those not in uniform, conserving materials was the name of the game. Utility clothing became the fashion, which meant simple silhouettes (to conserve fabric), limited clasps, buttons and zippers (to conserve metal), and man-made fibers (to save silk and wool for the military).

Wikimedia

Womens utility clothing

The men’s Victory Suit came in a synthetic wool-blend with a shorter jacket and limited colors (black, brown and navy). Gone were the double-breasted jackets, extra pockets, vest and second pair of trousers. Women’s dresses and skirts became tighter and shorter with all non-functional features virtually eliminated (ruffles, pleats, hoods, cuffed sleeves, etc.). Wool was to be saved for military uniforms, silk was rationed for parachutes, and chemicals formerly used to dye clothes were diverted for explosives. Women’s head coverings or turbans also became popular as they joined the workforce and needed to keep their hair from catching in the machinery (and hide messy or unwashed hair due to shampoo shortages).

A campaign of “Make-Do and Mend” was popularized and the “hand-me-down” trend, started during the Great Depression, continued. Unusable pieces were turned, with a government-approved pattern, into something new. If a woman was lucky enough to have a sweetheart with a used parachute, she could turn it into a wedding dress, dressing gown or even underwear.

Women’s nylons were also affected by rationing as it was used for parachutes, cords, ropes and surgical sutures. A staple of the 1940s women’s wardrobe, the price for stockings rose from $1.25 to $20 a pair on the black market. “Liquid stockings” was presented as a somewhat messier alternative8. This was a nude-colored makeup product that gave the illusion of stockings, especially paired with a eyebrow pencil “seam” drawn down the back. You could even have them painted on for you.

Come Visit

Looking for a unique Valentine’s Day/Weekend date activity? Bring your sweetheart to the Warhawk Air Museum to spend some time looking through our curated Valentine’s Day display and searching for unique toiletry items scattered throughout the museum. From touching letters of love, to treasures sent from loved ones overseas, we have everything you need for a truly special trip.

Resources

- Pallingston, Jessica. (1999). Lipstick: a celebration of the worlds favorite cosmetic. New York, NY: St. Martin's Press.

- ""Speak Softly and Carry a Lipstick:" Government Influence on Female Sexuality through Cosmetics During WWII." Niederriter, Adrienne. (2009). Retrieved February 2020, from https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/read/11635094/speak-softly-and-carry-a-lipstick-government-influence-on-female-.

- Women in Nazi Germany. (2020, January 28). Retrieved February 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Women_in_Nazi_Germany.

- Behind the Color: 1941 Victory Red. (2018, August 15). Retrieved February 2020, from https://besamecosmetics.com/blogs/blog/behind-the-color-1941-victory-red.

- Beetroot and boot polish: How Britain's women faced World War 2 without make-up. Lawrence, Sandra. (2015, March 3). Retrieved February 2020, from https://www.telegraph.co.uk/women/womens-life/11393852/Beauty-in-World-War-2-How-Britains-women-stayed-glamorous.html.

- Hair Has Long and Short History in U.S. Armed Forces. Dorr, Robert and Fred Borch. (2012, April 28). Retrieved February 2020, from https://www.defensemedianetwork.com/stories/hair-has-long-and-short-history-in-armed-forces/.

- Washington, not Paris, dictated fashion during World War II with rationing and restrictions. Blount, Jim. (2015). Retrieved February 2020, from https://sites.google.com/a/lanepl.org/jbcols/home/2015-articles/washington-not-paris-dictated-fashion-during-world-war-ii-with-rationing-and-restrictions.

- Paint-on Hosiery During the War Years. Spivack, Emaily. (2012, September 10). Retrieved February 2020, from https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/paint-on-hosiery-during-the-war-years-29864389/.

Happy Valentines Day to all at the Warhawk museum!

Good historical article

You should do more of these

Very interesting.

Thanks for the feedback Stanley! We would encourage you to check out our blog archive for more historical articles like this.