Clarence E. “Bud” Anderson, a pilot of the 357th Fighter Group with his P-51 Mustang, March 1944.*

Posted On: August 21, 2019

Clarence E. “Bud” Anderson can’t remember a time when he didn’t want to fly. Anderson was born on January 13, 1922, and grew up on a farm near Newcastle, CA. “The Sacramento valley was a major airway and all of the airplanes that would fly across this area would go practically over my house”1 says Anderson, but “it cost money to fly and that’s what we didn’t have on the farm”2.

As there was no way for Bud to learn to fly on his own, he looked into the requirements for military aviators. “I found out you had to have two years of college, you had to be 20 years old, physically fit, and unmarried.”2 “I had all of that except I didn’t have two years of college”1, so he enrolled in Sacramento Junior College where he serendipitously learned of the Civilian Pilot Training Program. This program was signed into law by President Roosevelt in 1938 after it was determined that the United States was woefully unprepared for an air war, with shortages in pilots, instructors and training craft. “For the price of $9.50 for insurance and my parent’s permission, I learned how to fly”1 observes Anderson.

Flying through flying school

Anderson received his private pilot’s license and got a job at an airfield in Sacramento, CA (now McClellan Air Force Base) as a civilian aircraft mechanic. “The war broke out in December 1941, I turned 20 in January, I went right there on the base and signed up at the recruiting office and seven days later I was gone into my flight training”1 recalls Anderson.

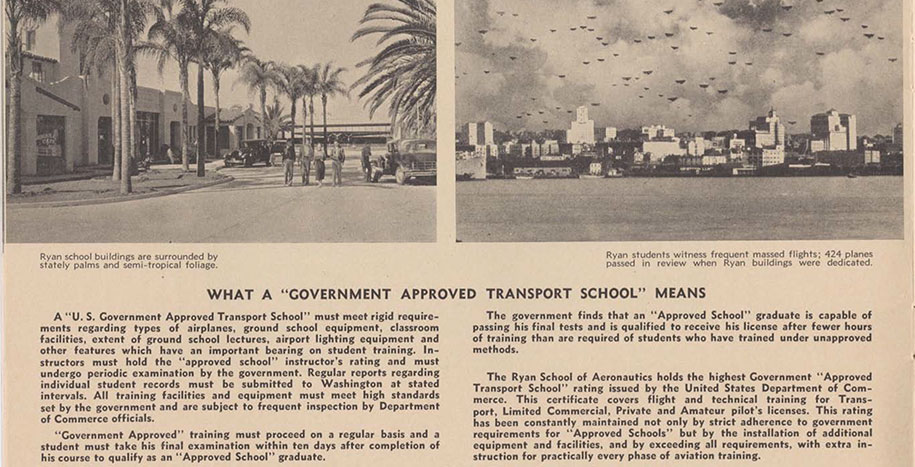

Source: UC San Diego Library Digital Collections

A page from a Ryan School of Aeronautics (Lindbergh Field, San Diego) pamphlet.

Anderson’s career in the Army Air Corps Aviation Cadet Program began at the Ryan School of Aeronautics in San Diego, CA where he flew the Ryan PT-22 Recruit. From there he moved to Minter Field in Bakersfield, CA for basic training, flying the Vultee BT-13. Advanced Flying School was at Luke Air Force Base in Phoenix, AZ where he graduated to North American AT-6s. Anderson “got his wings” and graduated September 29, 1942.

Because there were such shortages in pilots in every category (from bomber and fighter to transport), Anderson successfully convinced his instructor that he’d make a good fighter pilot. “I thought if I was in a single-engine, single-pilot airplane, I’d be in control of my environment, I’d be in control of my life. I’d be the pilot, the navigator, the gunner, the radioman, all the works. I wouldn’t have to depend on other people, a crew”2 muses Anderson.

Anderson was assigned to the Oakland Municipal Airport in a fighter squadron based at Hamilton Field. “We were the defense of San Francisco with P-39s, which seems kind of humorous in these days” he laughs. “When I got there it was only a year after Pearl Harbor happened and I can remember on the anniversary of Pearl Harbor, sitting on alert all night when they thought there was a big bunch of ships coming in toward the West Coast. We found out that it was the Navy and they didn’t tell anyone.”1

Right time, right place, right plane

“I was one of these guys that seemed to be at the right age, at the right time and I had all kinds of right things happen for me,”2 Anderson says. Instead of being sent overseas, he was assigned to a brand new 357th fighter group that was to train in the United States. “And why is that so good?” queries Anderson, “it put me on the ground floor for leadership, promotions, but the big thing is I got another training cycle and the more experience you have the better off you are.”2

Source: IWM

“Old Crow”: Captain Clarence A “Bud” Anderson has signed the image: “Just one more pass back & we’ll set course – Your pal, Andy.”

Another break came after Bud sailed to England and learned he would be flying the brand new P-51 Mustang. After suffering heavy losses attempting a strategic bombing strategy, the Army Air Corps changed tactics to utilize fighter escorts for their B-17 Flying Fortress bomber formations. Since Anderson’s unit was the next to get the P-51s (necessary for their impressive range), they got the job. None of the new unit had trained with, let alone seen, a P-51, but their work with the P-39s made it a fairly easy transition.

It was as a flight leader of these fighter escorts that Anderson began earning his fame as a “triple ace”. To be an “ace”, a pilot needs to shoot down five enemy aircraft in aerial combat. Anderson and his trusty P-51 “Old Crow” tallied 16 ¼ victories during his two tours of combat, making him the third leading “ace” of the 357th Fighter Group.

Why “Old Crow”? “Well, I tell my non-drinking friends that it was named after the most intelligent bird that flies in the sky. My drinking buddies all know that it was named after that good old Kentucky straight bourbon. It was the cheapest thing back then”3 reveals Anderson.

Source: IWM

Post war portrait of Bud Anderson.

Experience, Discover, Remember

After 30 years in the military, Anderson retired in 1972 with over 7,000 hours logged on over 100 types of aircraft. In 1990, Anderson co-authored the book To Fly & Fight—Memoirs of a Triple Ace (available for purchase and autographs at the Warbird Roundup). He has been inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame and International Air & Space Hall of Fame and accrued a number of decorations and awards, including the Congressional Gold Medal in 2015.

Join us at the 2019 Warbird Roundup for an incredible opportunity to learn from and honor living legend Col. Clarence “Bud” Anderson. Experience and discover all of the exciting tales and experiential wisdom that the last living WWII “triple ace” and highly sought after aviation and military speaker has to impart.

Source: IWM

Captain Clarence E. “Bud” Anderson sits on the wing of “Old Crow”.

Resources

- Cooper, D., & Walden, J. (2004, March 16). Clarence E. Anderson. Retrieved from https://memory.loc.gov/diglib/vhp/story/loc.natlib.afc2001001.12689/

- American Veterans Center. (2016, January 11). Full Interview: Bud Anderson (Part I). Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bifIJmQcI_4

- Kindy, D. (2018, December). Conversation with Flying Ace Bud Anderson. World War II Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.historynet.com/conversation-with-flying-ace-bud-anderson.htm

- * Header image source: Imperial War Museums — American Air Museum in Britain

Tags: Event|Veteran's Stories

Opens in new window

Opens in new window  Opens in new window

Opens in new window  Opens in new window

Opens in new window