Posted On: April 8, 2020

The Beginning

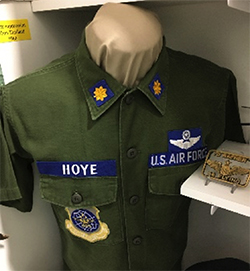

John Hoye was born in 1923 and moved to Idaho in 1934 from Winegar, Wisconsin with his sister and parents. After graduation from high school in Winchester, Idaho, John volunteered for the U.S. Army Air Forces (would become the United States Air Force) in March 1941. He entered Flying School as an Aviation Student in December 1941 and graduated under the Enlisted Pilot program as a Staff Sergeant Pilot in June 1942. He would eventually learn to fly his favorite plane: the P-38, a twin-piston-engine fighter. “Every time you advanced the throttles, you were treated to a WHOOM WHOOM. That really sounded like power!”

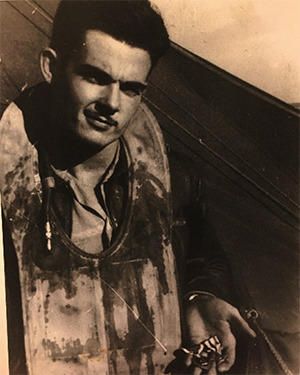

Too Close for Comfort—World War II

Due to a shortage of pilots, John trained to fly transport planes. He was dropping paratroopers over Italy when he was shot down on July 11, 1943, during the Sicily invasion. John recalls his injuries; “The blood is from head wounds, including shrapnel to the side of my face, arms, and an mg-bullet across my mouth, which splintered and cut off three teeth as well as a portion of my upper gum. Also had a piece of shrapnel in the cornea of my left eye and another piece embedded about 1/16 inch from the optic nerve.”

Despite numerous injuries, all of the crew, except one, either parachuted out or survived the crash landing. After being rescued, John received medical care for his wounds aboard the U.S.S. Neville and was sent back to his unit base, where he found himself listed as MIA (Missing In Action). Other pilots had reported his plane going down in flames. John was discharged from Active Duty (now an Air Force Reserve Officer) and received his first Purple Heart. He moved back to Idaho to start civilian life.

First Recall, My Country Needed Me—Korea

On March 10, 1951, as a part of the 91st Interceptor Squadron, John was recalled to active duty—to fly the F-86. He describes the plane as “sturdy, light on the controls, and with wonderful performance. It had a top speed in level flying of just under the speed of sound (approximately 667 knots or 767 mph) and could penetrate the so-called sound-barrier in a dive.”

As a pilot, John knew that they would soon be flying against Russian MIG’s. He heard about, applied for, and was selected for an elite training mission for top-notch pilots. A “TDY” (Temporary Duty) base was set up in South Korea so the pilots could train against the MIG-15 as well as other communist planes. After the TDY was completed, John returned to England.

While in England, John received orders for Korea. On the flight to Kimpo Air Force Base in Seoul, South Korea, John and others were much amused by “a very reluctant volunteer. He got drunk at every opportunity at stop-overs, and usually appeared every morning for take-off, with an ice bag on his aching head.”

In preparation, John completed survival training in case of capture by the North Koreans. The aircrews were confined in a replica of a prison in North Korea. John describes one “especially disagreeable portion” of the training: each person “was locked in wooden cases for several hours at a time. The cases, some upright and some horizontal or underground, were just deep enough and wide enough to pack a human in, and spacers were inserted beneath your feet to make the position a stooped, cramped one.” The forced position would cause leg and arm cramps to occur, and the men were also drenched in perspiration because they were in “full battle rattle” (full battle gear). The training was designed to be a psychological strain because the North Koreans would be using Communist torture methods, which attacked both the mind and the body.

In 1953, after arriving at Kimpo, John was assigned to the 335 Fighter Interceptor Squadron. On one mission, he saw a brown colored MIG-15 through the clouds and called to his wingman to watch out. He then called for Speed Brakes out and started a diving spiral to the left “with the intent of breaking out below the clouds and getting a shot at the enemy plane.” After bottoming out below the clouds at a very low altitude, the MIG was not in sight. John called for “speed brakes in” (to pick up speed) as they were over China’s side of the border and that was no place to loiter. They could see the muzzle flashes of a multitude of heavy enemy anti-aircraft guns positioned on the Suhio Dam on the Yalu river! John received a call from his wingman saying, “YOUR SPEED BRAKES ARE STILL OUT.” John then realized that his thumb had slid across a temporary guard that had been placed over a toggle (the guard was to be changed for a new standard switch between missions). Then John saw “a long uneven line of black puffs of exploding shells about 100 yards to our left” at the same altitude as his plane! He said, “I made sure to change air-speed and rate of the climb about every 2-3 seconds to confuse the radar gun laying equipment trying to get a bead on us.”

Both John and his wingman made it back to Kimpo with no further excitement. After landing, the wingman asked him, “Captain, are all missions like that?” John replied, “I sure as hell hope not!” Later he concluded, “that day over the Suhio Dam was probably my biggest contribution to the war effort, as it must have cost the enemy thousands and thousands of dollars for all the steel, they had fruitlessly thrown at us. But also, the temporarily jury-rigged Speed Brake switch could have made it a different story.”

After his assignment in South Korea was finished, John asked to be discharged from active duty. His wish was granted, and he again moved back to Idaho.

Uncle Sam Called Again—Vietnam

It was 1954, and once more, the nation would need John’s help. He did not hesitate when new orders arrived. This time he was headed to Vietnam.

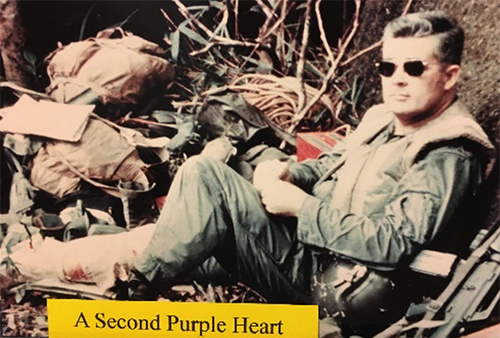

While attempting to evacuate four wounded Marines from the jungle about 12 miles southwest of Da Nang, John, piloting the HH-43F, thought that they were experiencing power failure. They had actually been hit by enemy fire.

The “Huskie” went down but everyone made it to the ground alive with only John and one other injured. Two rescue attempts were made that afternoon by a Marine HH-46 helicopter. The heavy ground fire would not let up, and both rescue attempts were aborted.

John, along with three other airmen, spent the night with the marines. Throughout the long night, John called in artillery so that the Viet Cong would not be able to set up firing positions. The next day, two Marine Sea Knight choppers were able to rescue both the Airmen and the Marines. John spoke for the group when he said, “Those Marines did a great job. It’s good to be back.” John was awarded his 2nd Purple Heart.

John received many decorations for his faithful service to his country. His medals include a Silver Star Medal with Oak Leaf Cluster, two Purple Hearts with Oak Leaf Clusters, an Air Medal with five Oak Leaf Clusters, as well as two Presidential Unit Citations and six Battle Stars.

Click to enlarge

If you would like to read more about John’s experiences, please read his memoir book Three Damned Wars Too Many, available at the Warhawk Air Museum.

If you would like to support our efforts and mission, there are several ways you can help: pre-purchase tickets (we will honor all online ticket purchases, regardless of expiration date), donate, or become a member or corporate member. Thank you for supporting the Warhawk Air Museum.

Learn more about our Profiles in Courage Project.

Tags: Korea|Profiles in Courage|Veteran's Stories|Vietnam|WWII

We have a lot of military heroes living here in Idaho. They should be congratulated on service rendered.

John is a Great Gentleman and Scholar. Their wasn’t anything he couldn’t do! Including build his own airplanes in his garage! He purchased the kit from Afton Aviation , Afton, Wyoming,, then fly there and ask ,, “how do you like it “! They loved the ‘alterations’ he made! A Great Husband, Father, Grandfather, and Great Grandfather!! A Great Man who Gave So Much to His Country👍🙏