Posted On: April 14, 2023

Joining the Royal Canadian Air Force: World War II

Herbert “Bud” Milligan was born in New Rochelle, New York on January 3, 1918. At the age of 19, he was busy racing cars on dirt tracks, but soon heard the siren song of another adrenaline-inducing activity. Bud wanted to fly! He began his flying lessons at Roosevelt Field in Long Island, New York in 1940. However, he soon decided that free flying lessons would be better, so in 1941, he joined the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF).

On March 28, 1941, Bud wrote to his parents:

“Therefore, my friends, I’m now with the Royal Canadian Air force. I had to take an oath to His Majesty the King, that I will serve him for not less than one year, in Canada, or anywhere he sends me.”

So Bud trained with the RCAF—basic training in Toronto and flight training in Dunnville, Ontario.

On November 25, 1941, Bud again wrote to his parents:

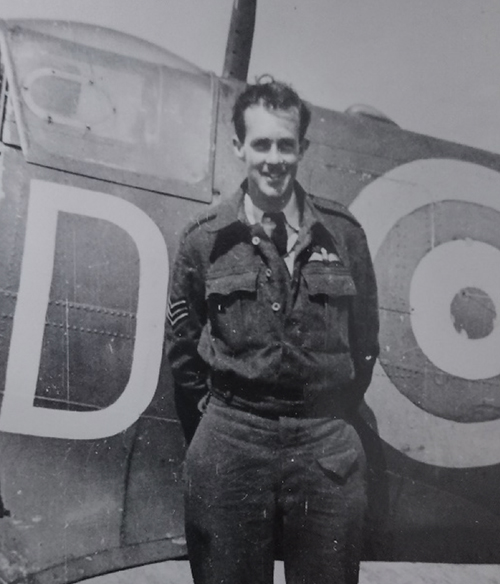

“Well I had my wings test yesterday and I passed it. At long last. After getting beat around for 8½ months or more I can wear my wings and sergant [sic] stripes.”

A Winter Voyage to England

On December 31, 1941—just weeks after the attack on Pearl Harbor—Bud was aboard a Swedish freighter on his way to England, but winter on the North Atlantic is hazardous. The waves were 40 feet tall and there was ice covering the ship and the ropes. Arriving in Liverpool, England, about ten days later, Bud went through more training. Since he was not Canadian, he was assigned to the Royal Air Force (R.A.F.). He started at the No. 9 Advanced Flying Unit in Hullavington, England in March 1942, then moved to the No. 61 Operational Training in April, where he trained on Spitfires. In June, he was assigned to the 243 Squadron (RAF) in Ouston, England. After training was completed, he was sent to Newcastle to do submarine patrol in the North Sea flying Hurricanes and Spitfires. It was only the beginning.

Volunteers Needed

In July 1942, volunteers were needed to go to the island of Malta, a small island in the Mediterranean just below Italy. Bud was beginning to find submarine patrolling too routine, so he signed up. On July 8, Bud and the other volunteers left England for Gibraltar. The Spitfires they were sent with were not able to fly all the way from Gibraltar to Malta, so pilots and planes boarded a small aircraft carrier: the HMS Eagle. Spitfires were not made to take off from an aircraft carrier and Bud and the others had no experience doing so—a new challenge to endure before even arriving. Six days later they arrived in Gibraltar and Bud finally saw what he was getting into.

In a letter written in August 1991 to Fred Gaffen, author of Cross Border Warriors, Bud writes:

“We arrived in Gibraltar [sic] on July 14, 1942, and after we had disembarked, we saw many badly wounded men also disembarking at Gibralter [sic]. I asked, ‘What in the world happened, was there an accident at sea?’ I was told that these poor devils were pilots returning from Malta. I was beginning to get the picture.”

The Dangers of Malta

Mussolini had joined the war on June 10, 1940, and the next day, Malta was attacked. The defense consisted of ten obsolete Gloster Sea Gladiators, hastily assembled from boxes. The island of Malta was a key point in strategy for both the Allies and Mussolini. For the Allies, a base on Malta was an “unsinkable aircraft carrier” (Winston Churchill) and meant that they could attack ships carrying supplies for the enemy, hinder the enemy’s movement in North Africa, and attack Italian naval and air bases. These movements, however, were met with constant counterattack, a campaign known as “The Siege of Malta”. Over a two year period (1940– 1942), 6,700 tons of bombs were dropped on the Grand Harbour area alone (on the eastern coast of the island).

Arriving Under Fire

Bud arrived in Malta in the middle of an air raid. The 30 Spitfires aboard the carrier were not armed due to weight restrictions for the carrier. Though they were quickly supplied with cannons and machine guns after landing, only 25 of the 30 Spitfires were left. Bud was told that the average life expectancy of a pilot on Malta was three months.

He was assigned to the No 229 Squadron for the Royal Air Force at Ta Qali Airfield. The squadron was kept very busy for the next three months going on air raids (Bud was in the 3000th Luftwaffe air raid) to protect the island, as well as bombing and shooting air bases in Sicily. They had to be ready to fight at all times, so they sat under the wings of their planes in full flight gear and a life jacket in the stifling Malta heat. Flight gear could not be reduced, however, as the temperature would drop to -20° F after reaching about 25,000 feet. When they leaned back in their seats, they could feel the ice crunching under their suits.

In a letter from Bud to Fred Gaffen dated August 1991, Bud writes:

“The food at Malta was not Gourmet [sic], but after watching the local Maltese cutting and eating grass, our daily ration of ‘Bully beef’ (Corned Beef), and one 2 oz. slice of bread seemed plentiful. Needless to say I lost weight, going from 175 lbs. to 128 lbs. during my stay there, which was not unique, everyone did.”

To Bail or Not to Bail

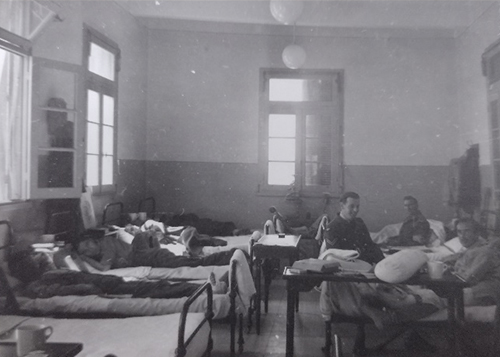

On October 24, 1942, fate struck. Bud’s plane was shot by a ME-109 (German Messerschmitt). Bud felt his boot filling with blood. He opened the cockpit to jump out (there was not an “Eject” option in his plane), but ultimately decided against it. Bailing out (the only alternative to going down with the plane) had its own risks as he could either be shot while parachuting down, or if he landed on land, he could be taken as a prisoner of war. Though the Spitfire was off-balance from being shot, he was able to land the plane back on the island of Malta. After landing, he discovered that he’d been shot in the ankle.

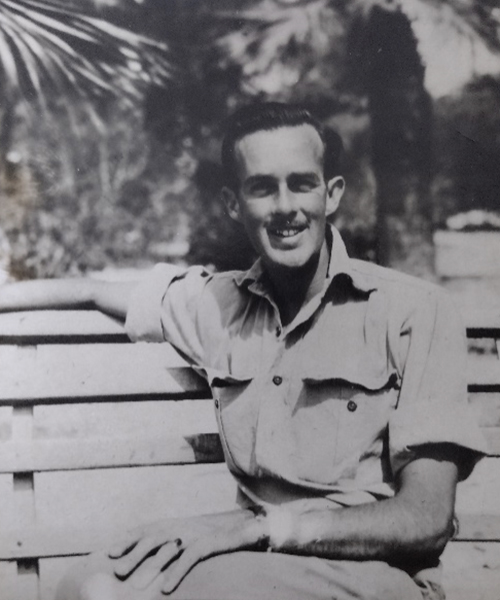

Bud spent the rest of his time in Malta at the hospital and, when he was well enough to travel, was sent to a hospital in Cairo, Egypt to continue treatment, remaining for five months. Around August 1943, Bud went back to Toronto to work as a flight instructor for Harvards (AT-6s) and Avro Ansons. He retired from the RCAF as a pilot officer in April 1945, where he had earned the 1939-1943 Star and Clasps, the Canadian Volunteer Service Medal and Clasp, the War Medal 1939-1945, the Pilot’s Flying Badge and the Malta Cross. The Malta Cross was reserved for those who had defended Malta.

A Career Far From Over

Bud continued working as a pilot and did not retire until 1985. He flew all over the world, working for Bell Aircraft Co., Pan American (Panagra), Standard Airlines, Trans International Airline and McDonnell Douglas Aircraft Co. He married his wife Doris in 1952 and two years later, they had a beautiful baby girl named Janet Marie. Jan is a volunteer at the Warhawk Air Museum museum. Bud passed away in February 2001, but his story will be forever preserved in a display here at the museum.

Resources:

- Gaffen, Fred. Cross-Border Warriors: Canadians in American Forces, Americans in Canadian Forces: From the Civil War to the Gulf. Dundurn Press, 2008.

- Milligan , Herbert. “Herbert ‘Bud’ Milligan.” Received by Fred Gaffen , 23 Aug. 1991.

- “World War II.” Visit Malta, https://www.visitmalta.com/en/a/world-war-2/#:~:text=Malta%20became%20a%20base%20for,the%20enemy's%20North%20African%20push.

what a great story. Having just read “the siege of Malta” Bud’s ‘evolution’ is fresh in my mind.