Fifinella, a character created for Roald Dahl by Walt Disney, was adopted by the WASPs as their official mascot.

Posted On: March 8, 2019

A brief history of women in the Air Force

The history of women in the Air Force technically begins with the National Security Act of 1947. This legislation formally separated the Air Force from the Army as its own branch of service. Shortly after, in 1948, Women in the Air Force (WAF) was formed with the Women’s Armed Services Integration Act, giving women permanent status in the Air Force. Esther McGowin Blake is credited as the first woman in the Air Force, having enlisted in “the first minute of the first hour of the first day regular Air Force duty was authorized for women on July 8, 1948”.Source

However, ignoring formalities, the history of women in the Air Force (or rather the US Army Air Force) goes back a bit further.

Previous to WWII, women served their country largely through the clerical and medical fields. The Army Nurse Corps was established in 1901 and the Navy Nurse Corp in 1908. During WWI, 21,498 women served as Army Nurses, 1,476 as Navy Nurses, and around 13,000 in clerical positions for the Navy and Marines.Source More than 400 were killed in action.

WWII was a turning point in more ways than one. Due to the large scale of the war and its high casualty rate, women took a more active role. Approximately 400,000 women served officially in non-combat roles including mechanics, pilots, clerks, nurses, ambulance drivers, and intelligence agents. 88 were taken prisoner of war and 16 killed in action.Source During this time there was a wave of newly formed groups for women volunteers, including Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps, Navy Women’s Reserve, Coast Guard Women’s Reserve, Marine Corps Women’s Reserve, Army Nurses Corps, Navy Nurses Corps, and, most excitingly for Kay Gott Chaffey, the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASPs). Not all of these groups received militarization, so many women were working as civilians.

Kay Gott Chaffey learns to fly

In 1940, while attending her second year at the College of Idaho in Caldwell, her friend got wind of a secret program that allowed one girl for every ten men to join the College of Idaho Civilian Pilot Training Class. Her friend’s guardians wouldn’t let her join, so Chaffey “dropped everything, hitchhiked 10 miles home to Nampa [her hometown] from Caldwell,” where her mother signed her permission slip. Chaffey joined a class of 19 men to learn to fly.

She earned her private pilot’s license and dropped out of school to focus on flying. “My instructor never told me I was any good, but he told my mother that I was a natural, whatever that means, and that I should continue on flying.” Her instructor arranged, and her aunt paid for, her membership in a club where she owned one-tenth of an airplane that she used to obtain her commercial pilot’s license as part of the Civil Air Patrol.

WASPs to the rescue

The creation of WASPs can be contributed to the separate efforts of pilot Jacqueline Cochran and test pilot Nancy Harkness Love. In 1939, Cochran wrote to Eleanor Roosevelt to suggest using female pilots in non-combat missions. Roosevelt introduced her to General Henry H. Arnold, but nothing immediately came of the suggestion. Upon the outbreak of war in 1941, both Cochran and Love submitted separate proposals to again encourage the use of women in the Air Force to fly as pilots in non-combat roles. They suggested that this would free male pilots for combat roles by using qualified women to ferry planes and tow drones and aerial targets.

Love’s proposal was the first to be accepted on September 10, 1942 with the creation of the Women’s Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron (WAFS).

The day before the official creation of the WAFS, Cochran returned from aiding the war effort in England and was angry that Love’s proposal had been accepted but hers hadn’t. She confronted General Arnold and her program and WFTD (Women’s Flying Training Detachment) was created on September 15, 1942. The women in WFTD trained on old planes and were known as the “Guinea Pigs”.

WAFS and WFTD became WASPs on August 20, 1943, after aggressive campaigning by Cochran to control all female pilots under a single entity. Love continued as the executive in charge of ferrying operations.

Training WASPs

Recruits were between the ages of 21 and 35, over 5’2”, were in good health, had 500 hours flight time and already had a pilot’s license (they could not be trained from “scratch” like male pilots were). Over 25,000 women applied to join; 1,830 were accepted and 1,074 completed training.

“My aunt called up from the office and said go out and get the evening post because there is a girl on the back, smoking a camel, and there is an ad beside her that says if you can fly and have $500, write or wire Jacqueline Cochran because women are needed to fly to leave men for combat. Well, I sent a telegram to Jacqueline Cochran, immediately…and by 2 or 3 o’clock I got a telegram back saying that if I arrived in 3 days I could be in the second group.

I was furious, just furious. If I’d known about it I would have been in the first group. And it took me 30 years to realize how lucky I was that I wasn’t in the first group. They had one potty on the field…the first group had a real rough time,” remembers Chaffey.

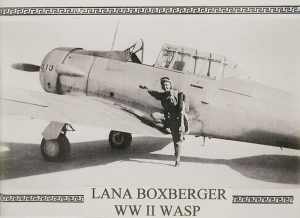

WASP recruits completed the same training as male Army Air Corps pilots and often also completed specialized flight training (Kay went to fighter school in Palm Springs). They spent 12 hours a day at the airfield, half flying and half studying. They knew Morse code, meteorology, military law, physics, aircraft mechanics, navigation, and other subjects.Source

After training they were stationed at 122 air bases around the U.S. and freed 900 male pilots for combat duty. They flew almost every type of aircraft flown by the USAAF during WWII as well as testing some that weren’t yet in use. Chaffey remembers flying 17 different types of planes including P-51 Mustangs, B-25 Mitchells, and the P-38 Lockheed Lightening. She recalls the purr of the Allison Rolls Royce twin-engines, “you oughta hear the sound, it’s unmistakable”.

WASP duties during the war involved ferrying planes from factories to air bases (women flew 80% of all ferrying missions), towing targets for live anti-aircraft artillery practice (the shots weren’t always on-target), simulating strafing missions, and transporting cargo.

Dissolution of the program

In the summer of 1944, when the war was beginning to wind down, a House bill to provide WASP with military status was defeated, stating that the program was unnecessary, unjustifiably expensive, and recommended that the recruiting and training of inexperienced women pilots be halted.Source The WASPs were disbanded in December 1944.

It is believed that the militarization bill failed due to lobbying by male civilian pilots and instructors. These instructors were losing their jobs as the war tailed off and fewer combat pilots were being trained. Fearing being drafted into the Army, they lobbied for the women’s non-combat pilot jobs.

“I was so disappointed that Congress would tell us to go home while we were still useful…and there was still a need for us to do the job we were doing. I was so disappointed that I never talked about what I did for years, I’ll bet 20 years I never talked about it at all,” said Chaffey.

After the program ended, the women were dismissed without ceremony and had to find their own way home. And, like Chaffey and many WWII veterans, many of the WASPs didn’t talk about their experiences. The records were sealed for 35 years, like many wartime files, and their stories were all but forgotten.

38 WASPs in total died in service of their country, but because the program was considered civilian, the military was not required to pay for the funeral or transport the bodies to their families. Many of the WASPs chipped in to pay instead. They also could not have the U.S. flag draped over their coffins. However, in the case of Mabel Rawlinson, who died in a night training accident, the family did so anyway.

Becoming women “in” the Air Force and flying high once again

In 1976, Women in the Air Force (WAF) was dissolved and a statement made by the Air Force that it was the first time women in the Air Force would be allowed to fly their aircraft. The thought that their service had been completely forgotten united the WASPs. They lobbied Congress in earnest to be militarized, with the support of Sen. Barry Goldwater, despite some opposition by the Veterans Administration, the American Legion, and the Veterans of Foreign Wars.

In 1977, President Jimmy Carter finally signed the bill. The women were issued Honorable Discharge certificates. They were awarded the WWII Victory Medal in 1984, and, in 2009, they were inducted into the International Air & Space Hall of Fame and awarded the Congressional Gold Medal by President Barack Obama.

In memoriam

In addition to finally receiving recognition from the U.S. government and military, others have memorialized the first women in the Air Force to fly in a variety of ways. In 1988, WASP member Florence Shutsy Reynolds took over WASP merchandising and designed a scarf for the women and other unique jewelry. In 1993, Ken Magid produced the documentary Women of Courage for PBS. In 2005, WASP member Deanie Bishop Parrish and her daughter opened the National WASP WWII Museum. And Kay Gott Chaffey, herself, wrote two books capturing the women’s stories: Women in Pursuit (1992) and HAZEL AH YING LEE: Women Airforce Service Pilot (1996).

Kay relates, in a 1999 interview for Living Biographies, “I wanted to write the book because the college girls that I got to know [teaching Physical Education at Humboldt State College] had such low aspirations… And even though there were more and more opportunities for women, I don’t think anybody dared to break out and really do what they were good at and I said, well, if I hadn’t really had a strong desire—there were so many obstacles in my way that—if I hadn’t really persevered, I never would have made it either.

Women should aspire to be more than they think they can be and they shouldn’t let disappointment stand in the way of achieving. That’s part of why I wrote the book.”

Although Kay Gott Chaffey passed away on August 21, 2017, you can find a display about her career, including her Congressional Gold Medal, at the Warhawk.

If you or a loved one are a veteran, come tell us your story!

The Warhawk Air Museum is committed to collecting and preserving veteran histories through its participation in the Veterans History Project. These interviews are powerful in their ability to bridge generational gaps and protect memories and experiences that will otherwise be lost.

Each and every story deserves to be heard.

Contact Heather Moore, 208-465-6446 or email [email protected], to inquire about setting up an interview.

Tags: Displays|Veteran's Stories|VHP

Opens in new window

Opens in new window  Opens in new window

Opens in new window  Opens in new window

Opens in new window