Posted On: May 6, 2020

It takes a certain kind of man to fly over Nazi-occupied Europe with an aircraft full of British paratroopers. It takes a very special kind of man indeed to crash-land that aircraft in a vineyard in the South of France and take to the fight on foot. This man was David Haggard and this unorthodox method of arriving on the scene was the result of volunteering as a glider pilot.

Fatefully blank film

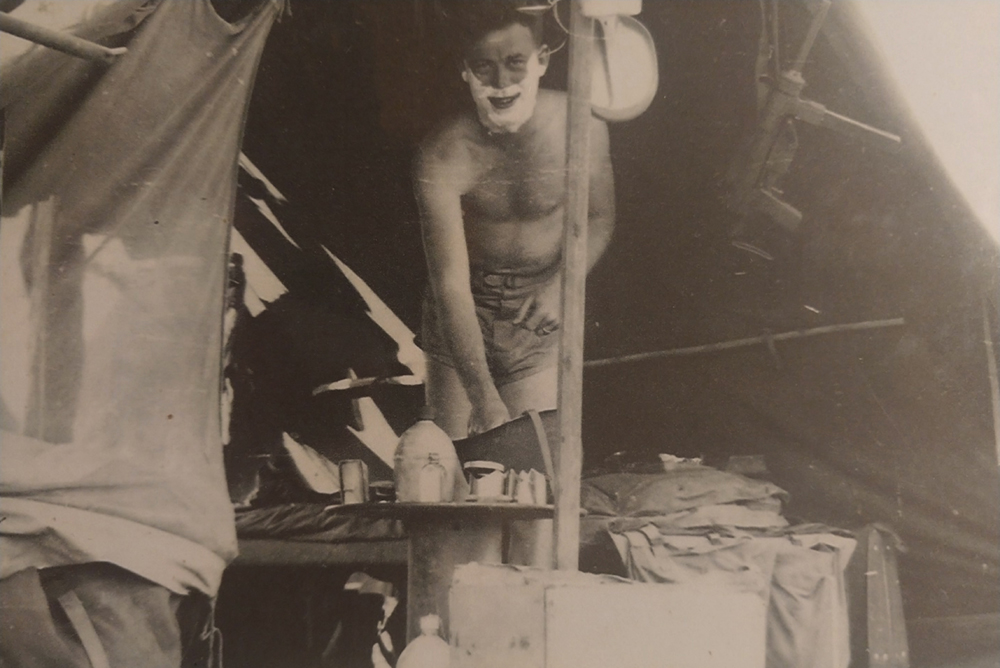

David Haggard was just a 23-year-old dishwasher when he enlisted in the US Army Air Corps in August of 1941. He’d grown up in Boise, Idaho, but with war on the horizon, David figured that he’d make a cracker-jack aerial photographer. With the United States not yet at war, his training class had to make do with antiquated equipment and a severe shortage of instructors. Nonetheless, life progressed amicably as David learned his craft. That is, until it didn’t. David still remembers when the day everyone had been waiting for came. He and his friends were playing volleyball outside the barracks when a bulletin came through the radio. The Japanese had bombed Pearl Harbor. The United States was at war.

Not long afterwards, during a training flight to film Yosemite National Park, David fatefully forgot to take the slide out of his camera. While scrolling through his now worthless film, he considered that aerial photography might not be for him. Shortly afterwards, as if by providence, he came across a notice on the camp bulletin board. It read “Learn to fly—Become a Glider Pilot.” David leapt at the chance and spent most of 1942 learning to fly small, underpowered aircraft and then Waco CG-4A gliders—aircraft with no engines at all! Come September, he was made a Staff Sergeant-Pilot and readied to deploy to the Pacific.

It would seem, however, that someone, somewhere changed their mind as Staff Sergeant Haggard found himself sent, not West, but East to England in April of 1943. Upon arrival, David and his fellows were thrown into infantry training alongside the 82nd and 101st airborne to prepare for the invasion of Europe. It was an excruciating waiting game. Everybody knew something was coming, but not when it would come. When the D-Day finally came, David found himself on standby. He was left with nothing to do but watch battered and broken airplanes limping back from Normandy crash landing on the runways and discharging their wounded flight crews. It was an experience that chilled him, but he would face his own trials before long.

The art of crashing

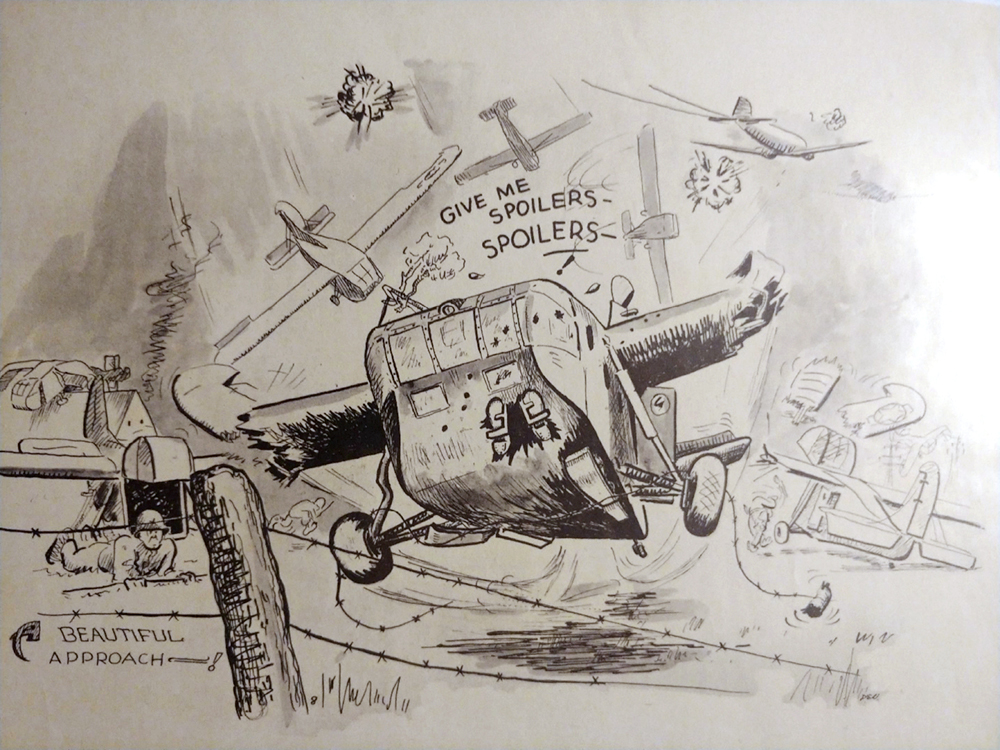

He was shipped to Italy with about half of his squadron to partake in Operation Dragoon: the invasion of Southern France. Before dawn broke on August 15, 1944, David, his co-pilot Fred, and a handful of British paratroopers loaded up their glider, shared a stiff belt of scotch, and gritted their teeth as the C-47 towing their glider took off for France. It was a harrowing flight. The glider next to theirs lost a wing during the flight—which didn’t inspire confidence in anyone in their rickety, unpowered aircraft —and as they neared the mountainous landscape into which they were to deploy, they came across a squadron of British aircraft pulling out. The British had decided the landing area was too foggy, but David and his comrades pressed forward anyway.

As they skimmed the treetops in the pre-dawn dark, they released their tow ropes and began desperately searching for the best place to land. The rough terrain offered little. With no other options, David settled on a vineyard. To his dismay, however, the vineyard was littered with anti-glider posts. Nicknamed “Rommel’s Asparagus,” these posts were the size of telephone poles and placed specifically to inflict the most damage possible to glider-borne infantry. With as much care as his adrenaline soaked muscles could manage, David guided his glider through the fog and obstacles towards the Earth—which is to say the posts sheared off both of the aircraft’s wings but he was able to crash the thing just right-side-up enough to walk away from.

Shaking themselves to their senses, they scrambled to get their cargo, a jeep, out of the wreckage of their glider. It was at this point that several of their British companions wandered down to a nearby farmhouse and came back with a German soldier bearing a white flag. The British relayed the German’s desire to surrender himself and his squad to the nearest officer. Not having an officer to produce, but thinking quickly, David pointed at a glider that had landed on a hill a few hundred yards away and declared “You’ll surrender to us right now or we’ll turn that howitzer on you!” The German sensibly agreed to David’s terms. Never mind that while the glider up the hill was indeed carrying a howitzer, it wasn’t actually carrying any ammunition!

His first experience in France completed, David would assist in the Allied efforts to secure the region before being tasked to the invasion of Holland in Operation Market Garden. Success there saw further involvement in the assault on Wessel, Germany. These operations brought their own moments of terror from gun battles with German machine gun nests to a rather unfortunate incident where one of his companions inadvertently flew their glider into a cow, but with this first hair-raising introduction to World War Two done, it was nothing David Haggard couldn’t handle.

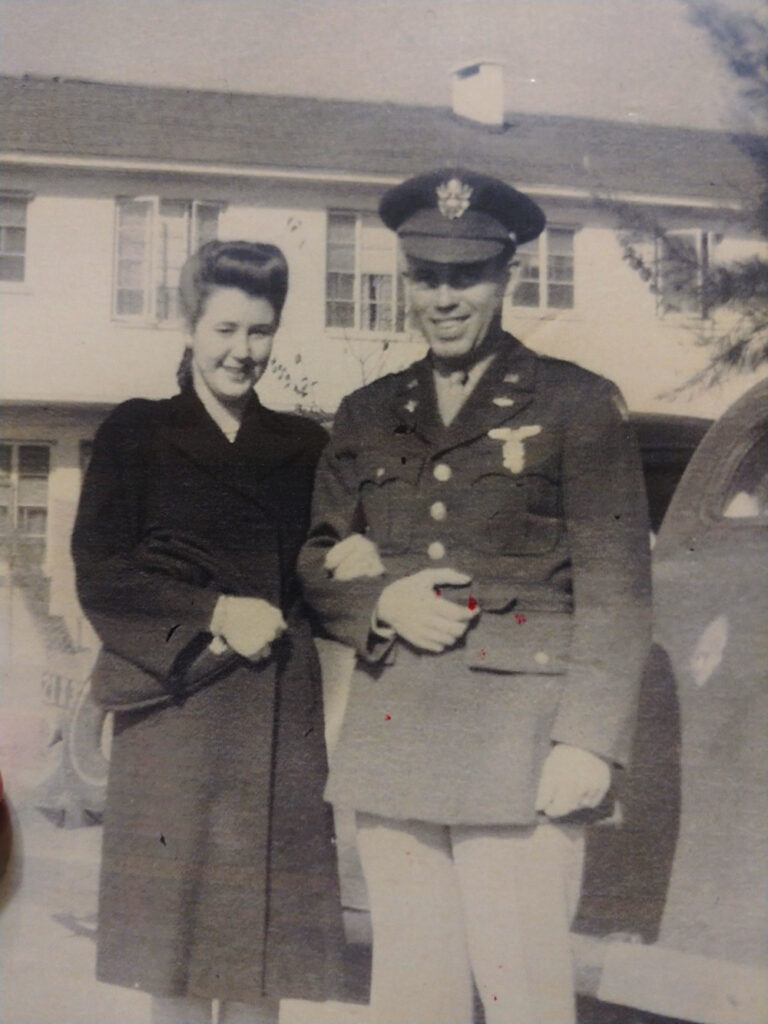

David returned to the United States after Germany surrendered. He married his sweetheart and steeled himself for relocation to the Pacific, but fate intervened once again to keep him home as the Japanese surrendered before his orders came in. After the war, he enjoyed a long and successful career working for a telephone company, from which he retired after more than three decades. He passed away in 2007 aged 89, a world away from the vineyard in France he had once liberated by crashing a glider into the middle of it.

To see a real WW2 Waco CG-4A glider fuselage like the one David Haggard flew, be sure to visit the Warhawk Air Museum. Visit David’s display in case #91 for more of his amazing story.

If you would like to support our efforts and mission, there are several ways you can help: pre-purchase tickets (we will honor all online ticket purchases, regardless of expiration date), donate, or become a member or corporate member. Thank you for supporting the Warhawk Air Museum.

Learn more about our Profiles in Courage Project.

Absolute bravery what our men and women accomplished during the war to keep us the land of the free. All are heroes. Thank you to each of them for their service. And thank you for sharing his story.

Quiet a story ..one of thousands about courage and sheer guts.

My own father was there .. D day. flying from a base in South England. Bomber Command.