Posted On: June 18, 2020

Article provided by Christian Zimmerman, M.D.

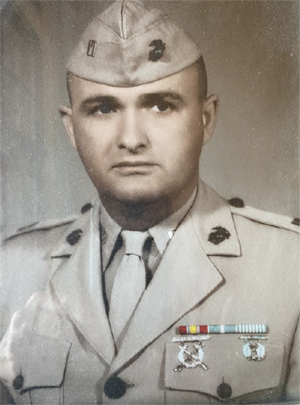

I was 11 when my father, Major Eugene Zimmerman, authored this Vietnam diary. He was interred in Arlington National Cemetery in 1996, but there is an unbeknownst historical narrative: a 13 month record of insights and sketches depicting the times and places of his combat experience. The following is a selected compilation from that 50-year-old manuscript with its extraordinary first-hand accounts logged through one Marine’s “Recording Eye”. ‘MOS 0203’

A change in the tide

Polled American opinion of the conflict in Vietnam prior to the Têt Offensive was mostly supportive, but after February 1968 the country was expectantly divided and by 1970 most felt this was a difficult, failing effort.1,2 Maj Eugene Zimmerman was on his third tour in Vietnam, having been part of an expeditionary force under both Presidents Kennedy and Johnson’s escalation from 1961 to 1967.2 His latest orders were a dual assignment as S-3 and later S-2 for the Da Nang Airbase. During this time period, he recorded daily notations and pictorials about such conflicts as Khe Sanh, Hue, Phong Le and Phu Bai. As the security officer and logistical coordinator of the entire airbase, home base for the 3rd Marine Division and Marine Aircraft Group 13,3 they endured numerous Viet Cong attacks with multiple casualties.

The following are a selection of excerpts and illustrative drawings from Maj Zimmerman’s diary recounting his 13 month tour of duty. The record outlines the day-to-day descriptions of the many responsibilities and locations during some of the fiercest battles of the Têt Offensive and the Vietnam War. It is also worth noting that his daily letters to my mom, and routinely to many others, were his sole manner of communication between himself and our family.

January 1968

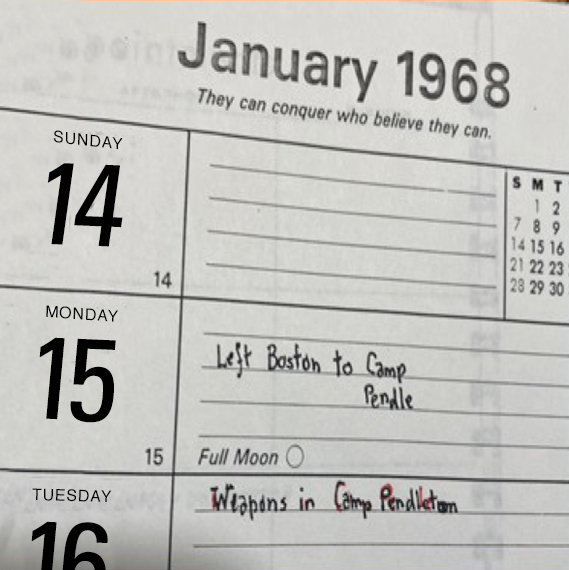

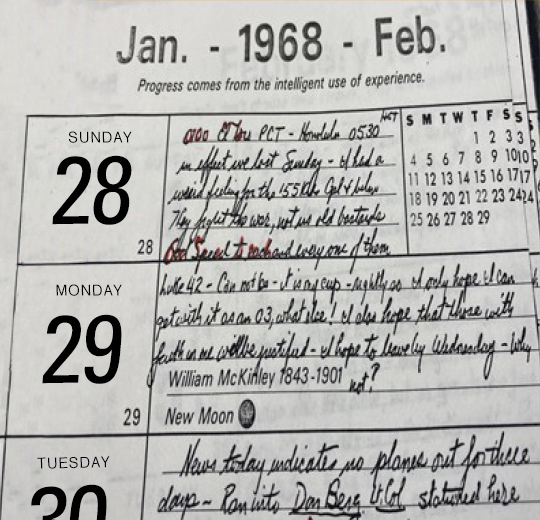

Jan 15: Maj Zimmerman departed for Camp Pendleton and arrived in Da Nang, South Vietnam two weeks later. He left behind a young family: his wife Joanne and their five children. The morning of his departure was incredibly difficult.

“I remember that morning quite vividly… I was 11 and old enough to feel the sadness and fear, sitting on the couch in my pajamas. My father came out of my parent’s bedroom, dressed in his Tropical Dress Uniform, his eyes were reddened and full of tears; He had just said goodbye to my mother. He did not expect to see me or any of his children that morning. He walked over to me and awkwardly said ‘You are the man of the house now, take care of your brothers and sisters for me.’ He hugged me, put on his cover, grabbed his suitcase and walked out the door. My Uncle Sam was quietly waiting for him to drive to the bus station for his departure to Boston.”

His return in February of 1969 would be equal in its emotion; substituting the grueling sadness of his departure for the complete elation and celebration of returning home and seeing his family.

Jan 29: A reserved man of internalized sentiment, my father’s religious beliefs were descendent and personal, yet his faith in God and humanity was evident as he wrote the one Biblical verse applicable to the uncertainty and human vulnerability he was about to encounter.

Luke 23:42-43 Then he said, “Jesus, remember me when you come into your kingdom.”

Jesus answered him, “Truly I tell you, today you will be with me in paradise.”

Têt Offensive 1968

The Têt Offensive was a major military campaign by the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) together with the Viet Cong (VC) against the United States and South Vietnamese militaries from January 30–September 23, 1968. Têt is the Vietnamese New Year.

The communist forces carried out the offensive in three waves: more than 600,000 communist forces attacking more than 100 American bases and South Vietnamese towns and cities.

50,000 communist forces were killed and the Viet Cong was severely depleted, which gave the Americans and South Vietnamese a tactical victory. Striking deep into American and South Vietnamese held territory, the communists showed that they were in the war for the long-run.

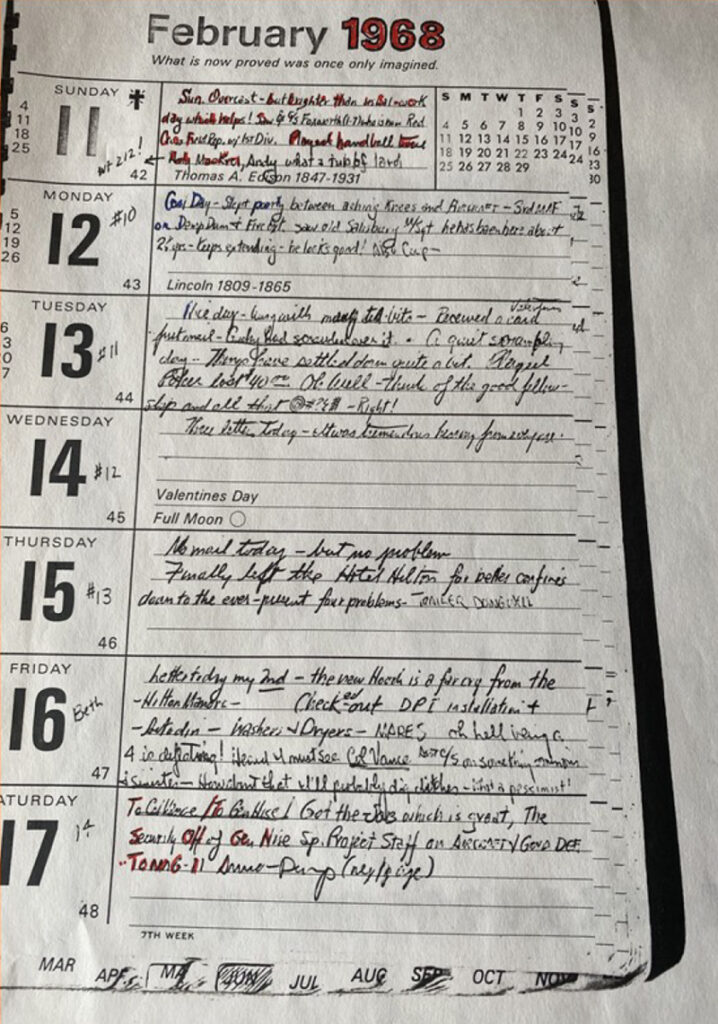

The Têt Offensive also demoralized the American and South Vietnamese forces, giving rise and impetus to the anti-war movement in the United States.4 The deadliest week of the Vietnam War for the USA was during the Têt Offensive (February 11–17, 1968), during which 543 Americans were killed in action, and 2,547 were wounded.4

| Battle Statistics 1968/Location | KIA | Wounded | Combatants KIA |

| Battle of Khe Sanh 6 (1/21/68) | 274 | 2,541 | 10,000–15,000 |

| Battle for Quang Tri 7 (1/31 – 2/6/68) | 18 | 137 | 914 |

| Battle of Huế 8 (1/31–3/2/68) | 216 | 1,584 | 6,155 |

| Battle of Signal Hill 9 (4/19–4/21/68) | 130 | 530 | 800 |

| Da Nang Airbase 5 (1/30/68–2/23/69) | 6 | 51 | not listed |

| Dong Ha 10 (4/30/68) | 81 | not listed | 600 + |

February – November 1968

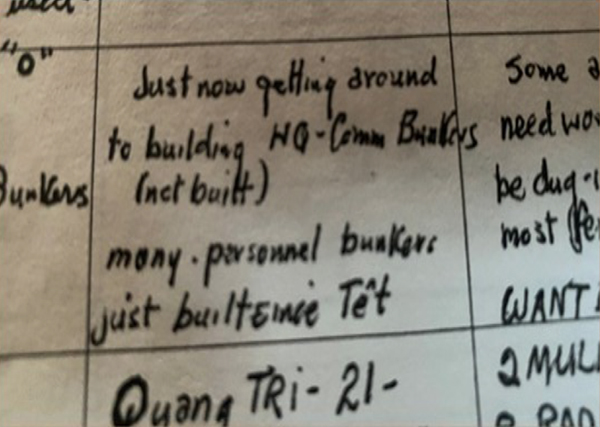

In the Têt spring of 1968, the North Vietnamese Army conducted 119 attacks on provincial and district capitals, military installations, and major cities in South Vietnam. The United States Marines maintained a supply base at Dong Ha in I Corps. It was in the northeastern area of Quang Tri Province. Late in April and early in May, the NVA 320th Division with 8,000 troops attacked Dong Ha and fought a rigorous battle against an allied force of 5,000 U.S. Marines and South Vietnamese soldiers. The North Vietnamese failed to destroy the supply base and had to retreat back across the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), leaving behind 856 dead. Sixty-eight Americans died in the fighting.

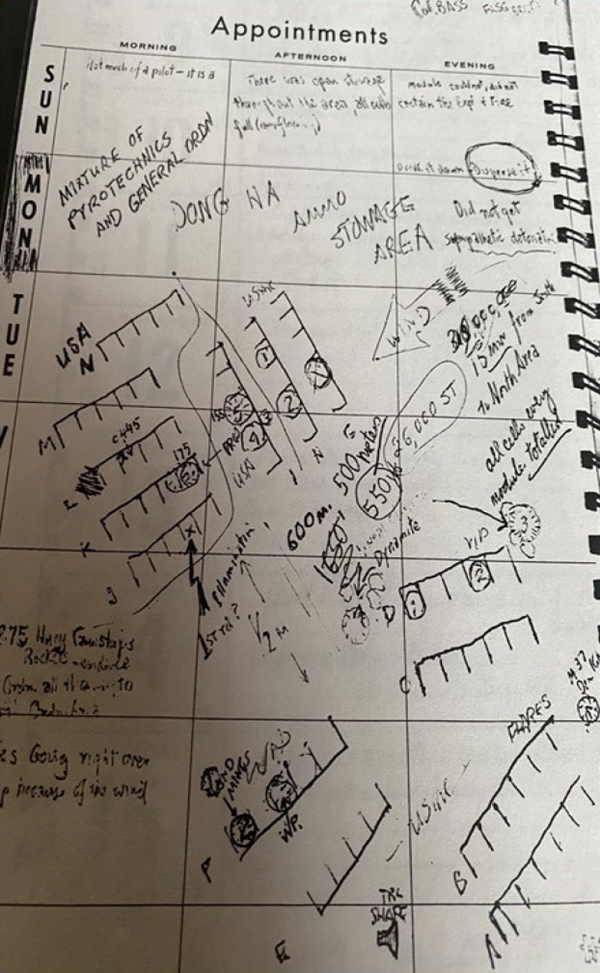

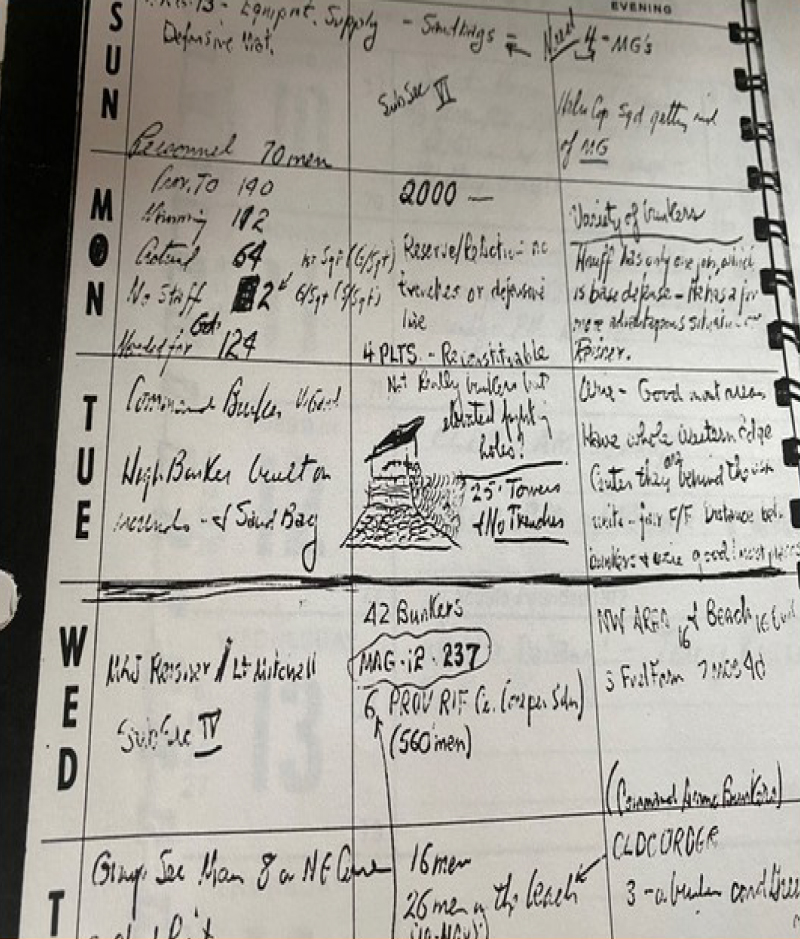

Shown here is a sketch of the security set up of the Dong Ha Ammo Storage Unit.

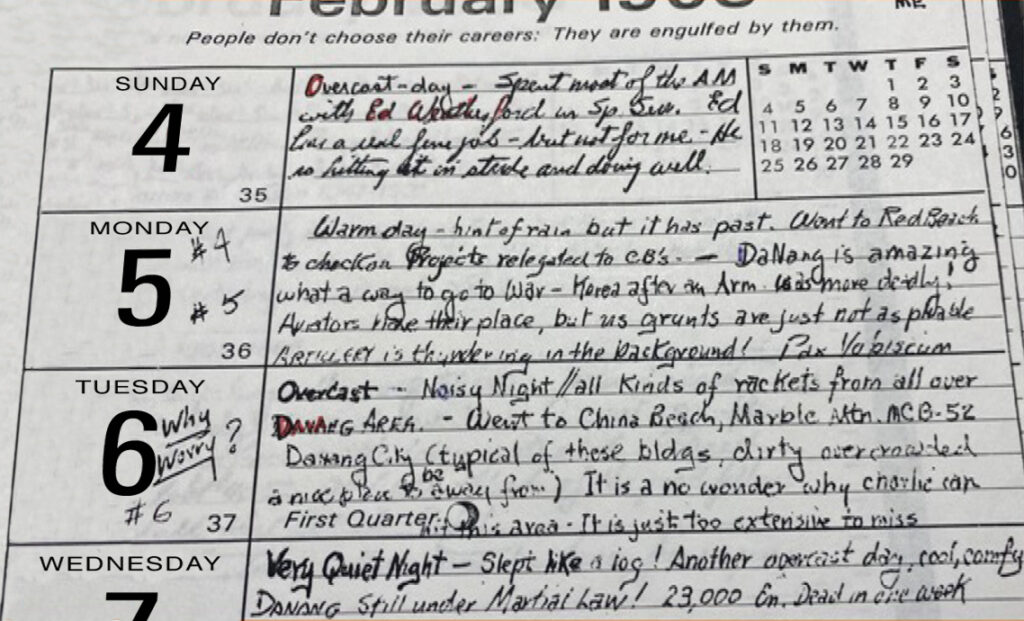

Feb 4–7: Discussion about weather and miscellaneous first impressions.

Feb 12: Not able to sleep because of aircraft flight activity.

Feb 14: Valentine’s Day “New letter today – it was tremendous hearing from everyone.”

Feb 17: Appointed Security Officer for the Marine Airwing.

The rapid defeat of the regimental size force that assaulted the coastal city of Quang Tri City proved to be one of the most decisive victories for the Allies during Têt.

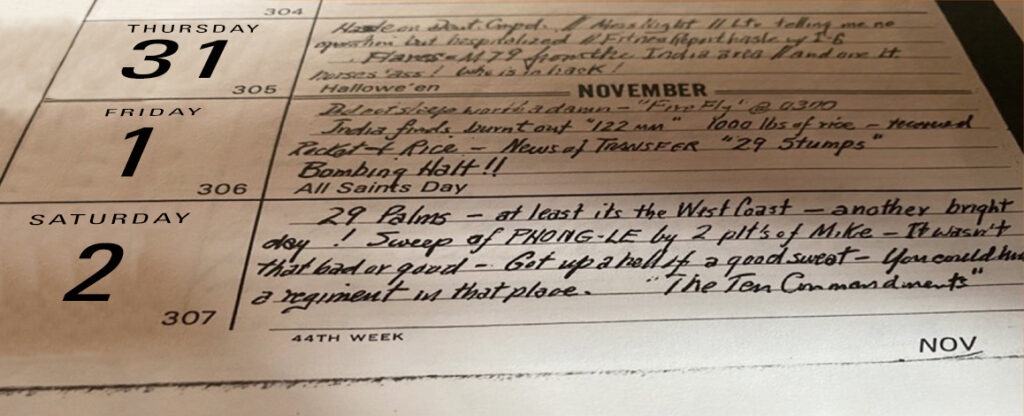

Oct 31: Flares in the middle of the night from M-19. Firefly “skyraiders” A-1 at 0300 hours. Most likely hitting enemy positions outside the airbase.

Nov 1: Mentions President Johnson’s bombing halt after the Paris Peace Accord.

Nov 2: Travels to Phong Le, Kham Dac as part of inspection of two platoons. Assigned to ‘29 Palms after his tour in Vietnam. Relief and anticipation.

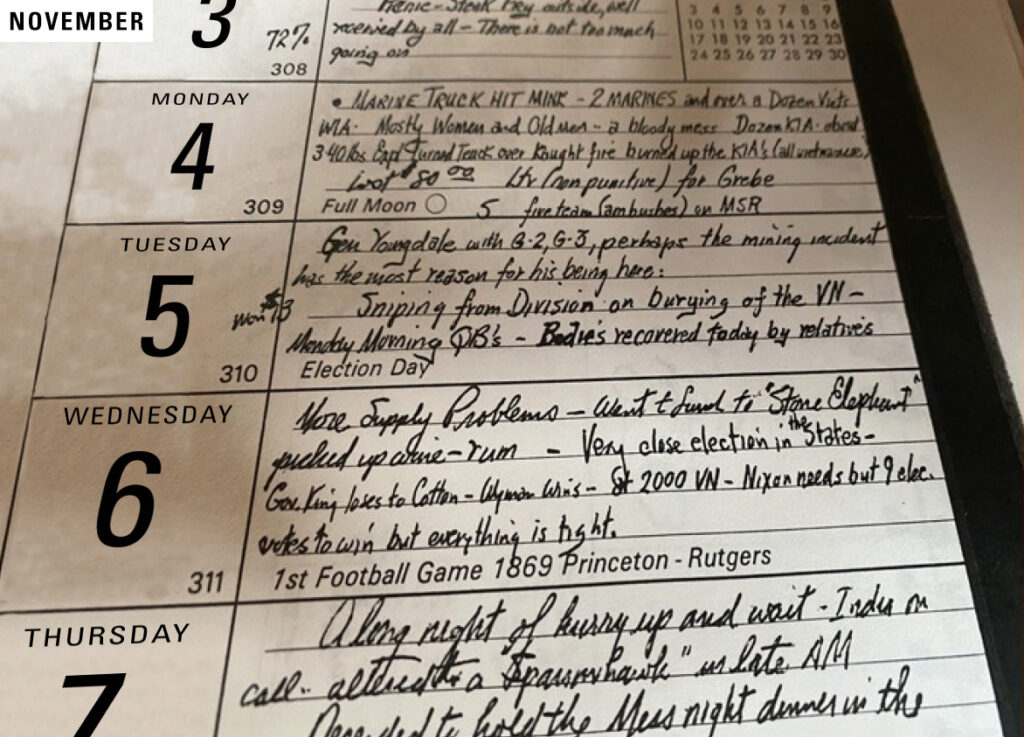

Nov 4: Land mine explosion (3 x 40 lb explosive) with numerous casualties both military and civilians.

Nov 5: “Big Brass” General Youngdale visits to take deposition of aftermath.

Nov 6: “More supply problems”. Had dinner at the “Stone Elephant” or Officers Club.

Nov 7: Operation “Sparrow Hawk” or helicopter based rifle teams became a common nightly occurrence as a methodology of enemy control.

Journal Drawings

Tuesday: Drawings of “high bunker built on mounds of sand bag”.

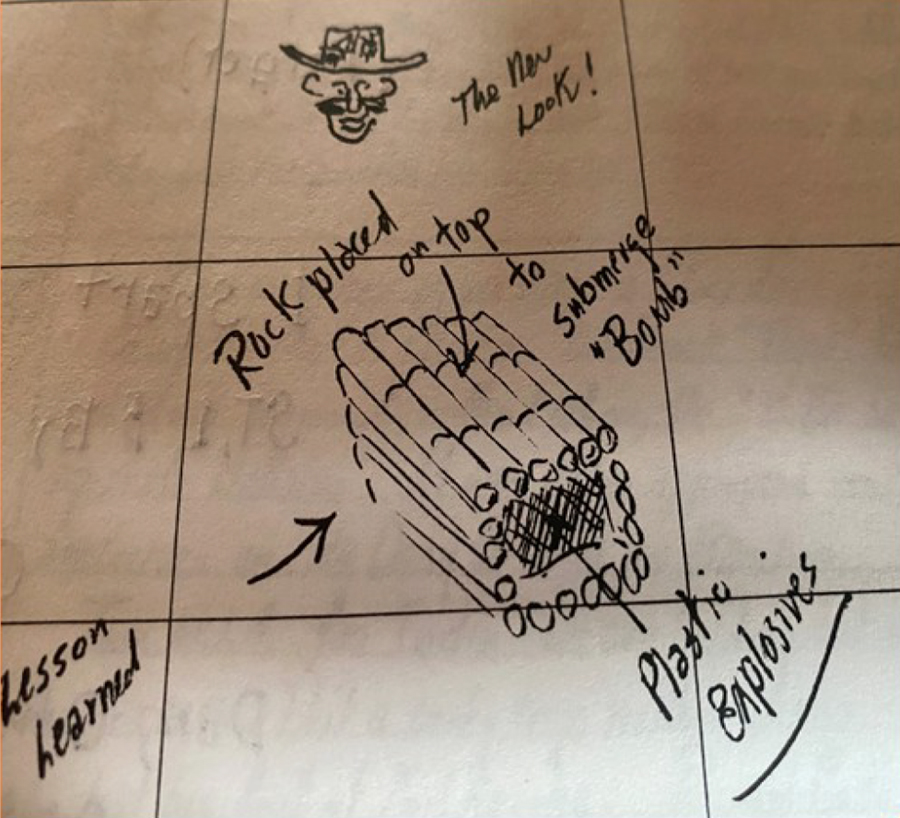

An illustration of an encountered “booby trap” filled with plastic explosives constructed by the Viet Cong.

Epilogue

It wasn’t until decades later, and investigating the many bases and outposts mentioned in this diary, did the direct impact of my father’s assignment in Da Nang resonate in its complexity and threat. The blending of logistics and security positions also carried the oversight of secondary bases such as Khe Sanh, Kham Dak, Dong Ha, Quang Tri, Monkey Mountain and Phong Le. These were locations of constant conflict and fighting during the Têt Offensive and Mini-Têt (May 1968) campaigns that saw the majority of American lives lost or wounded during any other period of the war. Neither had I realized the gravity of the Vietnam conflict and those that were assigned to the Airbase in Da Nang, which turned out to be the focal point for the North Viet Cong wanton takeover and attack.

My father’s return home transfixed the emotion of elation with the sadness of his departure. Little did we know, nor fully appreciate, the morbid arena of this conflict and harshest of human belaboring that so many endured. None of us had any idea of its extreme peril. And because of the mislaid sentiment here at home, he chose to neither discuss its horrors nor allowed it to distemper his life.

My father, and those with whom he served, believed in family, their country and their military duty. They were all great Americans.

Acknowledgements:

- Col. Pat Kilroy (Ret.) and the Warhawk Air Museum for the opportunity to share this history.

- Elizabeth O’Connor for collating pictures and fact.

- To all the servicemen and women who selflessly served this country and their fellow citizens at a time of great tumult and differing perspectives.

If you would like to support our efforts and mission, there are several ways you can help: purchase a ticket and come visit (we are open!), donate, or become a member or corporate member. Thank you for supporting the Warhawk Air Museum.

Learn more about our Profiles in Courage Project.

Resources:

- CBS News. (2018, January 28). CBS News Poll: U.S. involvement in Vietnam. Retrieved June 18, 2020, from https://www.cbsnews.com/news/cbs-news-poll-u-s-involvement-in-vietnam/

- Hall, Simon, "Scholarly Battles over the Vietnam War", Historical Journal 52 (September 2009), 81329.

- DK Publishing. (2017). The Vietnam War: the definitive illustrated history. NY, NY.

- Shulimson, J. (1997). U.S. Marines in Vietnam: the defining year, 1968. Washington, D.C.: History and Museums Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps.

- Fox, R. P. (1979). Air base defense in the Republic of Vietnam, 1961-1973. Washington: Office of Air Force History, United States Air Force.

- Battle of Khe Sanh. (2020, April 20). Retrieved June 18, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Khe_Sanh

- US Marines in Vietnam: The Defining Year 1968. (PDF)

- Battle of Huế. (2020, June 13). Retrieved June 18, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Hu%E1%BA%BF

- Battle of Signal Hill (Vietnam). (2019, December 16). Retrieved June 18, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Signal_Hill_(Vietnam)

- Đông Hà Combat Base. (2020, June 12). Retrieved June 18, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C4%90%C3%B4ng_H%C3%A0_Combat_Base

Thank you for sharing this. My husband was in DaNang 1969-70 with the Army, and his Marine brother was at Marble Mountain at the same time. God Bless.

Thank you. And thank you, Major Eugene Zimmerman. Words are not enough to express this family’s gratitude.