Posted On: April 15, 2020

A mission gone sideways

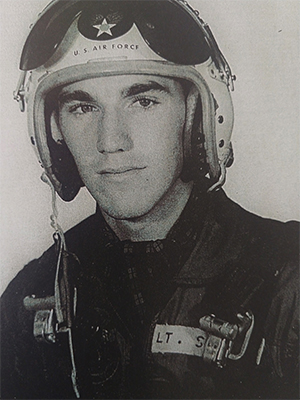

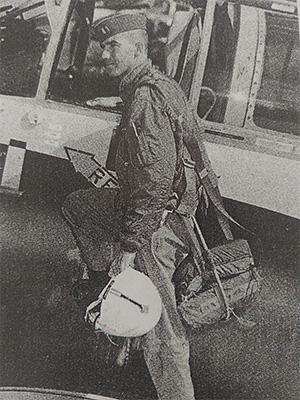

It was the 10th of September 1963, four days before his 27th birthday, and Lieutenant Thomas Schornak’s day was not going well. It had started with a fairly routine escort mission for a pair of Marine MEDEVAC helicopters. Having finished that, control gave him and his wingman, Frank Gorski, a close air support mission near the village of Ca Mau, Vietnam. His first run on the target had been a bust; a circuit breaker had popped and the can of napalm he was trying to introduce to the jungle had stayed connected to his aircraft.

Peeved, Tom had jinked his T-28 away from the stream of bullets coming at him and reset the breaker before going in for another run. The second try was much more successful, with the can deploying and defoliating its prescribed part of the Mekong Delta. Satisfied, Tom circled back around to drop his second canister. He came in fast and low enough to make eye contact with the Viet Cong soldiers as they levelled their rifles at him. A second dropped napalm can, a second satisfying boom, and he was streaking back towards the sky. Naturally, it was about this time that everything started to go decidedly sideways.

Tom had only just had time to register an acrid smell filling the cockpit of the plane when Frank’s voice called across the radio, “Lead! You are on fire! Lead! You are burning!” Any attempt for Tom to process this new information was cut short by a sudden spray of hot oil pouring out of one of the vents covering his instrument panels and burning his eyes. Fighting through the pain, Tom began wiping off his panels, but each just brought further bad news, so he gave up on that enterprise. Tom couldn’t see through all the smoke and oil, so he threw open the canopy which did improve visibility, but it also made the spray of hot oil significantly more unpleasant.

No good options

Tom took stock of his situation. His wounded aircraft didn’t seem likely to fly the 30 miles to the nearest friendly airstrip. Furthermore, he was flying a disintegrating airplane a couple hundred feet above a jungle inhabited by men he imagined would very much like to get their hands on him for the deliveries he had sent them just prior. Not that this mattered much, the T-28 had no ejection seats – the pilot just had to bail over the side – and he was probably about a thousand feet too low for that to be anything other than a death sentence.

All of which turned out to be purely academic, however, as his engine gave up. Tom’s world was a flurry of activity as he closed fuel sectors, pumped down flaps, and made correction after correction in a desperate bid to crash land his burning glider in a rice paddy he had flown over seconds before. As his plane slammed belly first into what seemed to be an all-encompassing blur of green paste, Tom realized two things. The first was that this was not, in fact, a rice paddy. Rather, it was a cane field which meant that instead of landing on two or three-foot-tall rice stalks in shin-high water, he was landing in four- or five-foot water with canes sticking up about six foot above that. The second realization was that, while he had no pitch or roll control, his rudders still worked. Figuring this would either slow him down or give him something to do until he died, Tom began to wrestle with the controls. Mercifully, the plane began to slow, but only slow. Suddenly, it slammed into a wall of earth dividing the field from its neighbor and everything went dark.

Tom awoke to the sound of .50 caliber fire. After a moment of confusion, he realized it was his own .50 caliber fire – his hand had squeezed on the throttle trigger as he blacked out. Bemused by this, he leapt out of the aircraft, which was beginning to sink into the muck. He instinctively checked his rear cockpit for his Vietnamese observer. It was empty, but Tom had no time to think about that. (It turned out the observer had taken the opened cockpit and accompanying spray of oil as a cue to jump out of the aircraft. His chute had opened only just in time and he landed in a banana field where he ditched his uniform and blended in with the locals.) He couldn’t see any hostiles, but Frank was flying back and forth strafing the trees a few hundred yards in front of him and Tom figured that Frank probably wasn’t doing that for the heck of it.

There would be relief sent, a company of South Vietnamese Marines would probably be parachuted in to even out the fight by sometime next morning. But next morning was an awfully long way away – and the Viet Cong weren’t. Resigned, Tom grabbed an M2 Carbine and a few 30-round clips out of the now mostly sunken wreckage and slunk off into the vegetation to await his fate, a trail of oil tracing his path. His odds did not look good.

Fortunately, Tom and Frank were not the only pilots in South Vietnam and by now the air was buzzing with T-28s and B-26s. One of these happened to fly by a dirt strip in the center of Ca Mau and noticed a brand new UH-1A Huey Helicopter – one of the very first in Vietnam – sitting on the dirt strip. By a stroke of luck, Brigadier- General Richard Stillwell was there being briefed by his subordinates. The Army pilots were contacted and without hesitation took to the air. They found Tom as he emerged from the undergrowth covered in oil looking “like someone who had just survived a freighter sinking.” He clambered onto the landing skids of the helicopter and the crew pulled him inside. Finding him unhurt, but tired and thirsty, they gave him a canteen and sat him on the floor. They couldn’t have him soiling up the seats of the General’s plush new helicopter after all!

A happy ending

Tom immediately penned a letter to his wife and children, letting them know he was safe. He would stay in Vietnam for the remainder of his tour and fly more than 40 more missions. In 1966, he was reassigned to be the Assistant Air Attaché to Burma where he spent more than a decade providing valuable training and organizational expertise to American and Thai air missions. After the conclusion of American involvement in Vietnam, Tom was crucial in the efforts to recover prisoners of war and missing personnel, both living and otherwise. His efforts were recognized by the State Department for their great value and helped pave the way for normalization of relations between the United States and Vietnam. He retired a Lieutenant Colonel, having served his country for 20 years.

If you would like to support our efforts and mission, there are several ways you can help: pre-purchase tickets (we will honor all online ticket purchases, regardless of expiration date), donate, or become a member or corporate member. Thank you for supporting the Warhawk Air Museum.

Learn more about our Profiles in Courage Project.

Wow, what an amazing story. I’m currently deployed and fly fighters overseas, what Lt Col Schornak experienced is incredible. I’m truly thankful for his service and I love reading these amazing recounts of heroism. Makes me proud to be an American!

Excellent story. I enjoy them all