Posted On: February 22, 2024

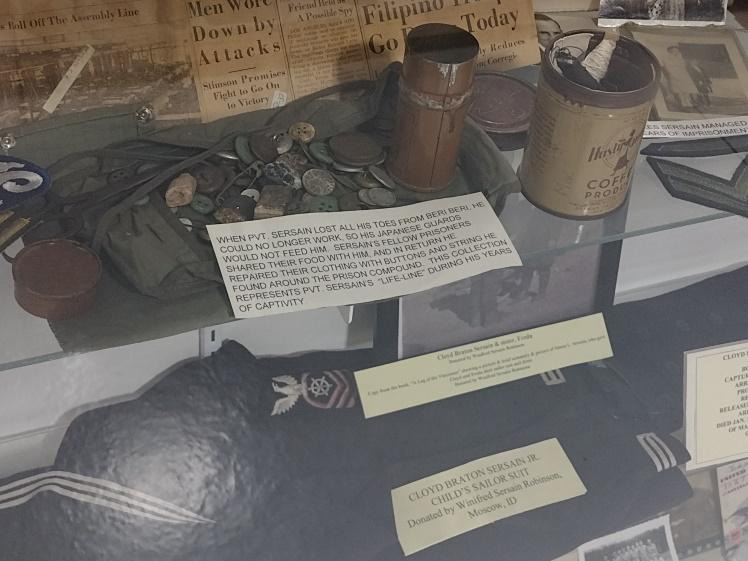

In the first hangar of the Warhawk Air Museum sits a display filled with ordinary, unassuming items: buttons, a sewing kit, letters, photos. Items that give us a glimpse of a young man’s life of survival and hope as a prisoner of war in Japan.

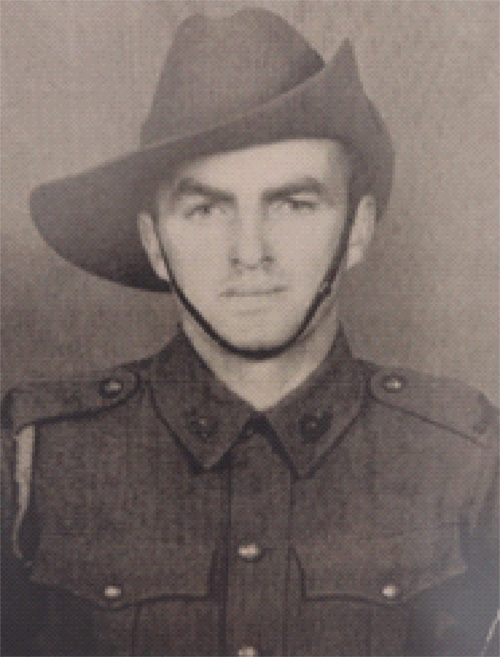

Cloyd Braton Sersain, Jr.—known as Braton to his friends and family—enlisted in the U.S. Army in January 1941, a month shy of his 23rd birthday. World War II was already in full swing in both Europe and the Pacific, but the Japanese wouldn’t bomb Pearl Harbor for another 11 months. The United States had yet to declare official involvement.

In September 1941, Braton was stationed at Fort Mills in the Philippines and could feel trouble brewing. In a letter to his family he shared his uncertainty stating, “Things are sure in a bad way now & no one in the service knows what’s coming…we might be in China by the time you get this. Sure wish it would either happen or blow over. Don’t think anything will happen here unless Hitler takes Corg [Corregidor]…”

On December 7, 1941, U.S. Naval Station Pearl Harbor was attacked by Japan, devastating the naval fleet stationed there. The next day, Congress declared war on Imperial Japan and the battle for the Philippines began. On May 6, 1942, Braton was captured by the Japanese and sent to Yodogawa, a prison camp just north of Osaka, Japan where prisoners were used as labor by the Yodogawa Steel Company. For nearly a year his family didn’t know if he was dead or alive, but continued writing him letters hoping he would receive them. Their letter dated August 1943 was full of encouragement: “Dearest Braton: we are still hoping and praying that you are well and safe. And that we will soon hear from you. Also that you have heard from us…Be hopeful, and remember we are all praying for you.”

Three days later his family received a letter from the War Department saying their son was a prisoner of war. Soon they began receiving letters from Braton letting them know he was okay and that his health was “usual” and “Don’t worry for I am being well taken care of…I pray to God to be with you all soon. Wishing all a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year. Keep praying and may God bless you all.”

It couldn’t have been farther from the truth. Braton had been transferred to the Akenobe Branch Camp where prisoners were used by the Mitsubishi Mining Company as laborers in the Akenobe Copper Mine. On August 15, 1945, Japan surrendered, bringing an end to the war in the Pacific. The next month his family received a telegram that Braton “was returned to military control.” He was coming home!

His letters began to detail what his life as a POW had really been like. The first month he was imprisoned he had worked, but then for the next 17 months he was unable. In the winter of 1942, he became very ill with malaria and beriberi—a disease caused by vitamin B1 deficiency causing impairment of the nerves and heart. His case was so severe that both feet were partially amputated. Known for his sense of humor, Braton wrote “They say if you wish long enuf [sic] for anything you’ll get it & I remember wishing many times I didn’t have any toes now there [sic] gone & don’t even miss them…” Braton’s shoe size went from a size 13 to a 6.

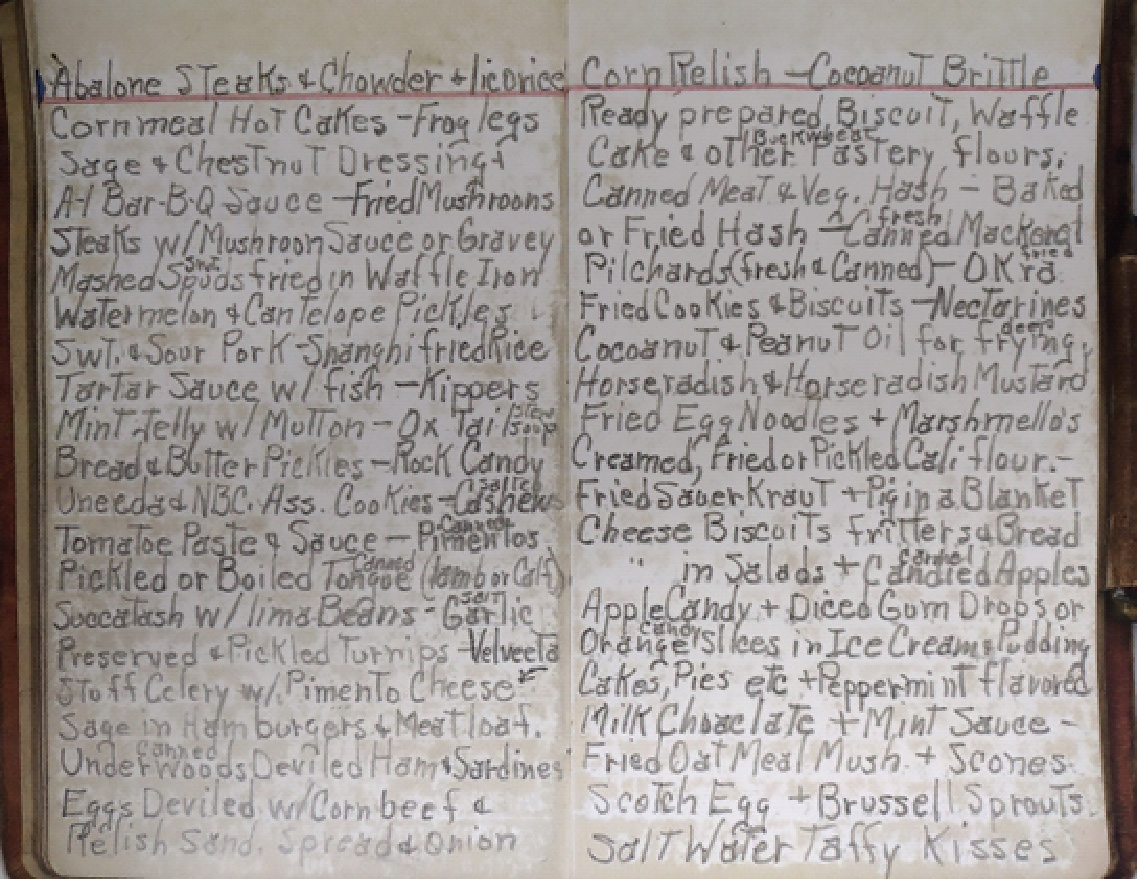

In September 1945 he wrote to his mother that she “…almost became a gold star mother the first winter was in Japan…Went from 186 to 80 lbs in 10 days.” He had spent time at Kobe Hospital where experiments were being conducted and had been poked so many times by needles that he felt like a “pin cushion.” To pass the time, he listed in his journal foods from home he missed.

Because he was too sick to work, but busied himself fixing the clothes of other prisoners, sewing on buttons when asked. Food was scarce and being ill did not help. His September 28, 1945, letter talked about the food they ate and sometimes had to steal—items like whole meat blubber and liver, horse, porpoise, squid, insects, seaweed, kelp, octopus, moss, snails, mussels, shark, fish, and even boiled cow and horse bones. In later letters he described how they slept on the floor and were eaten up by fleas.

After liberation, Braton was sent to Tokyo, then Okinawa, and then Manila, Philippines. In his letters home he said, “We get fed 5 times a day & all you want in between. Soon be up to 185 lbs again.” Finally, he returned to the United States through Pearl Harbor, then on to San Francisco, Tacoma, and finally home to Idaho. It was while in a hospital in San Francisco that Braton marveled to his family, “…Had first fresh milk since March 1941 2 qts [sic] & cottage cheese boy is it good.”

By the time his service was over, he had received a Purple Heart, five ribbons, four Presidential Citations with two bronze oak-leaf clusters, a Good Conduct Medal, one hash mark or service stripe indicating his years of service, seven overseas bars for his time in a theater of war, and corporal stripes. Braton was looking forward to the future and spending his back pay on new clothes, a Ford, and a visit to his sweetheart, Clara Johnston in Florence, Colorado. Luckily, Clara was able to come see him once he was home.

Braton also planned on keeping in touch with Simon McCloud, a fellow POW who became a close friend while they were imprisoned. Sadly, Braton passed away on January 14, 1946, from complications of malnutrition. His friend Simon wrote to Braton’s mother, “…I can’t express in this letter how hearing of Braton’s death has affected me—I had looked forward to seeing him again. He was a swell fellow, and I will never forget him—We fought and suffered together. All the fellows depended on him for a word of cheer and good humor.”

Tags: POW|Profiles in Courage|Purple Heart|Veteran's Stories|WWII

I grew up in Australia and lived just across the street from a Returned Serviceman’s Club. Many of the vets were WW2 troopers who fought in Malaya, Singapore or on the islands north of Australia. Many had been prisoners of the Japanese primarily in Changi. I grew up hearing the stories of the privations these men suffered as prisoners of the Japanese. Braton was a very tough man to have survived the horror of the camps. Thanks for his story and all the profiles in courage. Bless them all. Lest we forget