Posted On: August 13, 2020

On September 1, 1943 three Red Cross girls (Hortense Addison, Katy Groves, and Betty Heath [Oberst]) and about twenty GI’s boarded a plane in Chabua, Assam, Northeast India only to be told that one engine would not start. “That’s especially important to know ahead of time when you are going to be flying 14,000 feet on a C47 without additional oxygen and with radio contact only at the beginning and ending of the flight,” Betty explained. As they unloaded the plane for repairs, one bedding roll flew open—much to the embarrassment of Hortense as some of her personal items came into plain view. Betty, while laughing, helped to “save” Hortense. Finally, they re-boarded, took off, and four hours later landed at the headquarters of the world famous Flying Tigers 14th Air Force, just three miles from the town of Kunming, China. Her role, according to the Red Cross, was to run clubs for the morale of the men.

The Training

For several years Betty taught and worked for the YWCA and in February of 1943 she started her Red Cross career. That was the year—at the YWCA in Yakima, Washington—that Betty would meet the love of her life, Joe Oberst, a young technical sergeant. Listen to Joe describe the meeting:

Betty credits Eleanor Roosevelt, who was the head of the Red Cross, for encouraging her to “sign on.” Betty found a pamphlet recruiting Red Cross women overseas to run clubs or to work in hospitals. It was not long until she was asked to go to Washington, D.C. for interviews. When the meetings were over, she was handed a “long list of things I should have” and told to return in one week. When remembering her training, Betty recalled:

“When the other recruits and I returned, we were straightaway assigned a destination, but it was kept secret from us. Some left immediately while others went through two weeks of procuring uniforms, learning military customs. Some of us waited and waited as long as three months, never knowing from day to day if someplace would be Iceland or South Africa.”

Sixty of “the girls” were told to “keep their mouths closed about departure,” which was an easy job considering that they had not a clue where they were going. But, Betty remembers,…

“After about a week, the ladies entered a bus in the back alley for departure. Half of Brooklyn was there to wish us good luck. Big secret! We then were driven to a barn-like structure and walked down a gangplank with no goodbyes or confetti.”

They were on the newest of luxury liners, the America, now called the West Point, a troop transport ship which held 10,000 soldiers.

The Voyage

at the Warhawk Air Museum.

Betty remembering her voyage said:

“On board a sailor asked me to follow him to ‘my’ stateroom, and so I did – as did the twelve girls behind me – to a tiny cabin with three or four bunks to the ceiling. With thirteen women to one bathroom, allotted one hour of water in the morning, and one hour at night (per day for all of the women), we moved fast, giving up any privacy and tripling up, three minutes in the shower and so forth. Aboard, there was no air conditioning, (as the) portholes had been welded shut, and lights turned off at 8:00 p.m. No smoking was allowed on deck after sundown, and we had to go to our cabins. I crawled into a bunk with my suitcase, bed roll, and life preserver. As the girls chatted in the dark and told funny stories, I thanked God that none of us had claustrophobia!”

After about 30 days on the ship, the 10,000 individuals (including 60 Red Cross workers and 100 nurses) arrived at Bombay, India, many with violent dysentery. Five of the Red Cross ladies, Betty included, were asked if they would volunteer to fly the mountains over northern Burma and set up clubs in China. Of course all five volunteered and three caught a ride on a bomber. Betty and Katy Groves had to find their own transportation. One pilot said he could take one of the two ladies, and so, after a coin toss, Betty found herself stashed in the back of a cargo plane carrying wicker furniture.

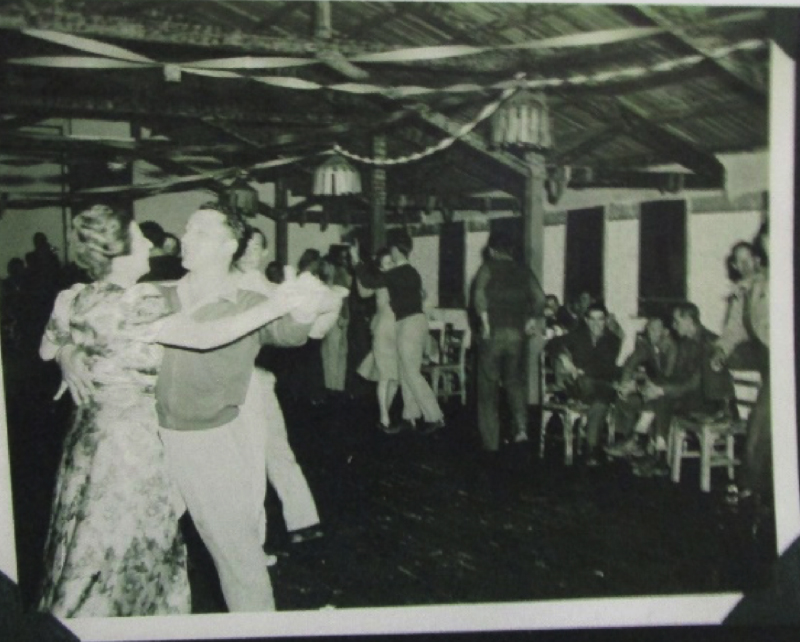

The Club

For two years, at different times, Betty was given three identical mud-brick, T-shaped buildings to fix up. At first, she tried to decorate with yards of indigo dyed cotton. Beautiful blue curtains, pillows, and refurbished benches with straw stuffing spruced up the place. Then a monsoon hit with rain, rain, and more rain. When Betty finally went back to work, everything had turned to a soggy blue. The floors, walls, and horrible-looking furniture were all soaking wet due to a leaky roof!

Betty remembered another “disaster”

“The disaster of disasters happened when I tried to brighten up one of my clubs. We had 90 chairs made and lots of benches and tables. I thought it would help if they were painted. Some kind soul ‘acquired’ a barrel of airplane paint, and after all of the painting, the furniture still looked exactly like the camouflage color it was meant to be. So, I decided to go to town and buy some varnish since there didn’t seem to be any other paint available. After returning with the varnish, and with the help of the men, ‘brightened up’ everything in sight. It was a success… until about two days later. Mrs. Kerr (head of the clubs for China, India, and Burma and who had attended the opening) became terribly sick and itched all over. For months afterward, she was still using bottles of calamine lotion. Gradually, one GI after another came in bandaged. I went to the hospital for a week myself for a terrible rash. No one told me that the base of the Chinese varnish is sumac, a second cousin to poison ivy! Needless to say, we had to sand off every bit of furniture.”

Another adventure started innocently enough but soon changed dramatically. It involved an old gravel truck at night with one dim headlight, no brakes, a Chinese driver who was not used to driving, and a plane. Listen to the Warhawk Air Museum’s Sue Paul read from Betty’s writings for the story:

Babysitters Needed!

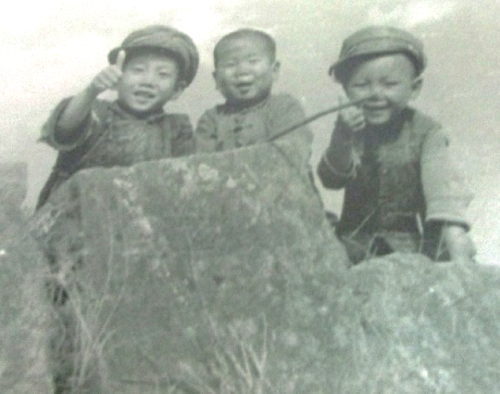

The day after Christmas 1944 started on a wrong note. The Japanese were heavily bombing American bases, and there was little to cheer up the men. The phone rang and a sergeant at the field waiting-room shack said that an American plane had just arrived full of about 30 orphaned babies being escorted by two utterly exhausted missionary women as they were moved step-by-step to safety in India. Betty was asked to help out:

“I decided that with that many babies, I could use some help, so I asked a couple of GI’s to go with me. In their wisdom, they said, ‘Why don’t we bring the babies here where there are lots of babysitters?’ We took trucks to the field, and a few minutes later, we opened the door and in came, either crawling, waddling, or carried, thirty babies. The homesickness and blues seemed to vanish, at least for a little while. The men held the babies, changed them, and fed them. Three sergeants spent the whole afternoon with a three-year-old. We fixed hot cocoa, soup, and cookies, and many of the men gave the children things that they themselves had received from home. I felt it was a God-send. When enough places with missionaries were finally found in town where the children could be cared for, we all said goodbye, thankful for a much happier Christmas.”

Returning to the U.S.

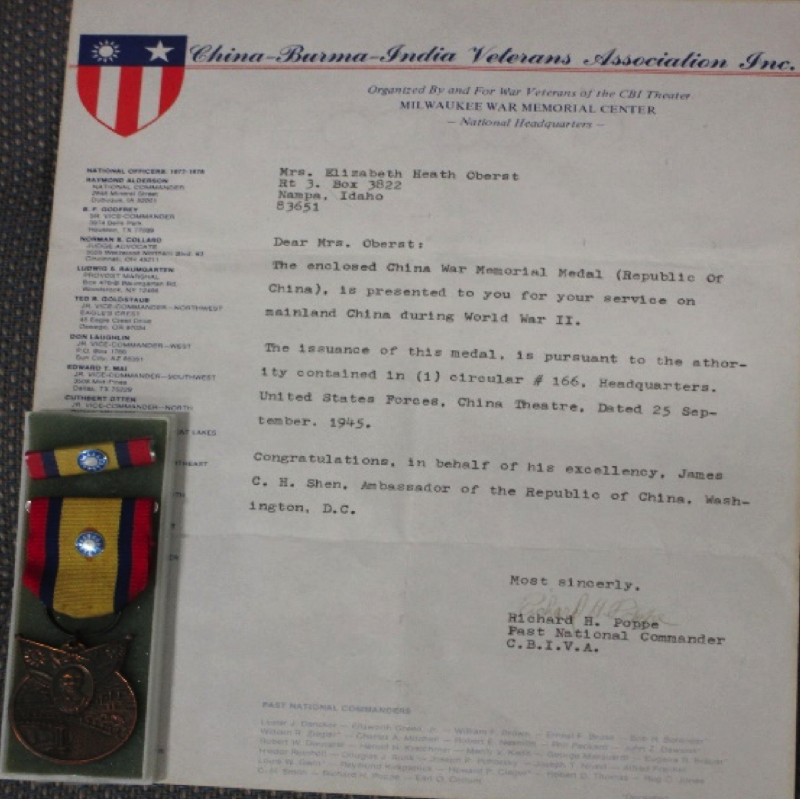

In May 1945, Betty returned to the U.S. with a smaller group of Red Cross workers, some very tired missionaries, and GI’s on a small transport ship landing in Long Beach, California, to “a good welcome.”

In 1953, 10 years after their fateful first meeting at the YWCA in Yakima, Betty married Joe Oberst. Joe agreed to help his dad for one summer in Nampa, Idaho. Listen to Joe describe the farm where the Oberst’s would raise their three daughters.

On their farm listening to the crop dusters working the fields, Betty would remark:

“Sometimes, when I hear the crop dusters in their propeller planes flying over, my mind goes back to those two years living on a field where planes came and went every three minutes or less. It was the end of the world, where the ATC (Air Transport Command) planes from New York to Miami, Brazil, Accra, Africa, across Asia, India then across the Himalayas unload, and after a cup of coffee, turn around and make the trip home.”

Joe left an incredible legacy in Betty’s name at the Warhawk Air Museum. The next blog will investigate his gift in more detail, so keep an eye out for it.

The Warhawk has more information on this and hundreds of other equally inspiring stories.

Tags: Displays|Profiles in Courage|WWII

I’ve known about the wing and her name. And she had a very deserving person. Thank you for this bit of her bigger story. It’s definitely news worthy.

Thank you. The Warhawk is full of stories.

Incredible story! Thanks for sharing these adventures.

There are still many stories to tell.